Herding 1440 Programs: Automating Large-Scale Codebase Changes for BCtCI

Introduction

I've spent much of this year herding a collection of 1440 small programs for BCtCI.

We have 288 problems with solutions in 5 languages:

- 19k lines of Python (65 average)

- 29k lines of Go (102 average)

- 26k lines of JS (90 average)

- 30k lines of C++ (104 average)

- 32k lines of Java (110 average)

- 26k lines of markdown write-ups (91 average)

These solutions and markdown write-ups are combined into 1440 language-specific markdown write-ups which are accessible for free through the book's online platform (bctci.co). A dropdown allows you to change languages. For example:

To the point of this post, I often need to make global changes that touch every problem. For example:

- Ensuring every markdown write-up includes the tests at the end.

- Ensuring that the tests are consistent with the constraints in the problem statement.

- Adding an entire new language (Go).1

- Ensuring that the implementations match the book.

- Fixing language-specific things, like ensuring we are using proper types, or that no JS solution relies on arrays plus

shift()instead of a proper queue. - Populating metadata for each problem, like which tools it uses (for my Toolkit-X project).

You get the idea.

The changes are usually trivial but hard to automate. It feels like managing a herd of 288 problems, where every so often I need to nudge all of them to go from one state (or pasture) to another.

In this post, I'll go over how I made this work more manageable (more "agentic") with LLMs, prompts and scripts included.

How the system works

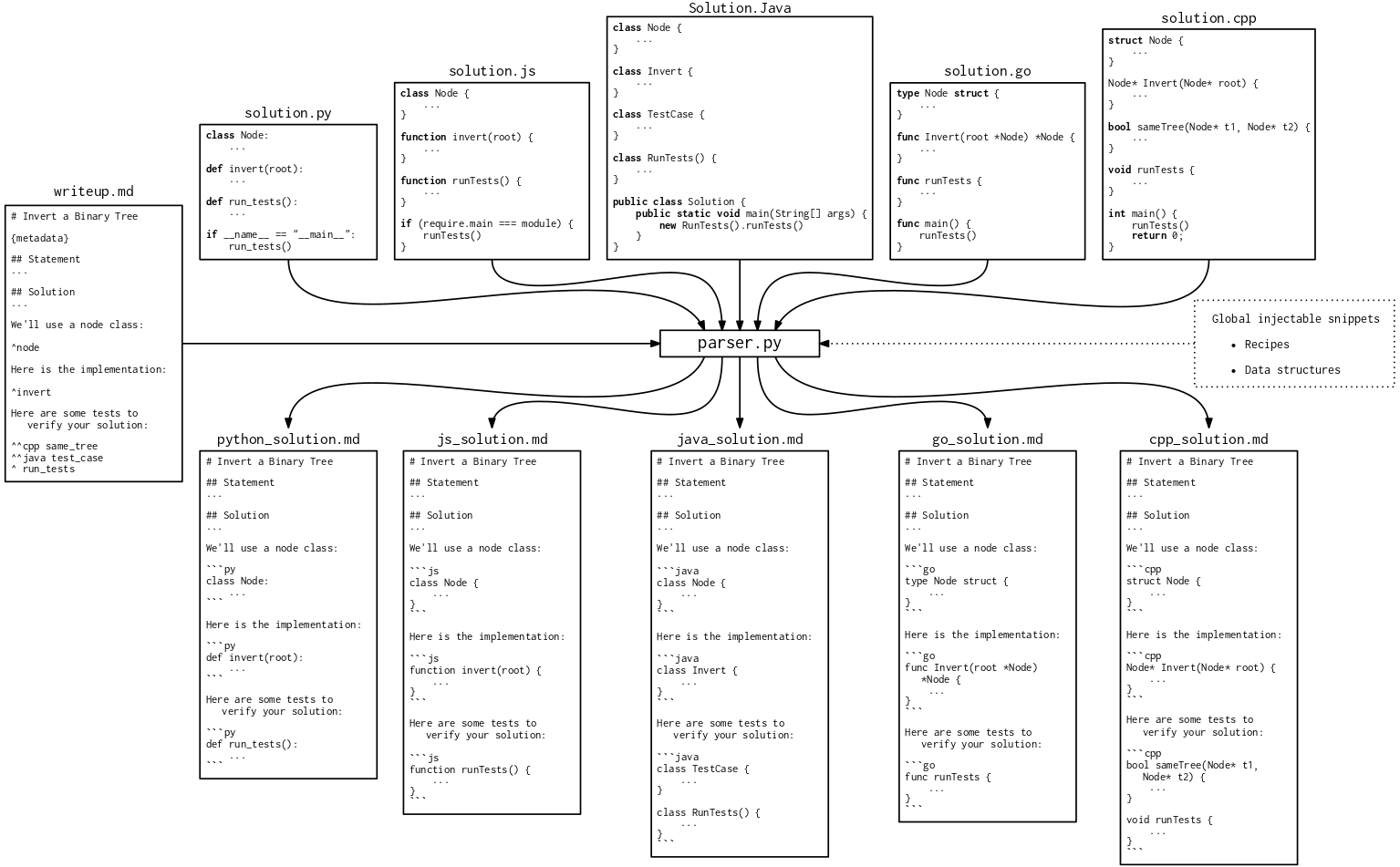

First, let's talk about how the code is structured and used.

This is relevant because we don't just need LLMs to produce correct code. We also need it to be aware of special rules that may sometimes not be the most idiomatic (like the fact that the top-level entities must match across all languages - more on that later).

The challenge is having code that is (1) tested, and (2) appears in a markdown write-up.

It's not straightforward to test code embedded in a markdown file, but we didn't want to duplicate the same code across a source file and a markdown write-up. We also didn't want to duplicate the explanation from the markdown across 5 language-specific markdowns.

So, for each problem, our constraint was to have one file per language and one markdown file without any code.

We structured the code for each problem and language as a single-file program including the main solution, any alternative solutions, and the tests. The solutions are mostly self-contained.2

It would be easy to simply append each language's source code at the end of the markdown write-up to create the language-specific markdowns, but we wanted more flexibility.

We want to be able to have smaller code blocks throughout the markdown. We may have something like:

Here is the first solution:

CODE

Here is an alternative solution:

CODE

Here are some tests to verify the solution:

CODE

To support this, we added a special syntax with ^ to the markdown files to indicate where the code should be injected:3

Here is the first solution:

^brute_force_solution

Here is an alternative solution:

^binary_search_solution

Here are some tests to verify the solution:

^run_tests

Then, I wrote a script that, for each problem:

- Receives

solution.{py,js,cpp,java,go}andwriteup.md. - Runs the tests in each language.

- Parses each solution to detect all the top-level entities (functions, classes, types, etc.), including the line numbers where they start and end.

- Injects the code into the markdown file at the appropriate places to produce the language-specific markdowns:

{python,js,cpp,java,go}_solution.md.

Those language-specific markdowns are then displayed in the book's online platform.

The main downside of this approach is the constraint that "all languages must have the same top-level entities". Languages differ in how they structure code, name things, and rely on helper methods.

Some parts, like matching camelCase and snake_case names, are straightforward. Avoiding helper methods or types is harder.

One way we dealt with this, which is a bit hacky, is by using nested functions. For example, Java may have a class with three methods; in Python, this may become a function with three nested functions, even if it's not the most idiomatic.

Sometimes, it's impossible to align the top-level entities. For example, JS doesn't have a built-in queue, so any time we use a queue, we need to insert a queue implementation but only for JS. Thus, we also added a special syntax to the markdown files to inject certain lines only for certain languages.4

We found this to be the best tradeoff between flexibility and maintainability.

Here is the code for the parser.5

In short: the parser stitches source code and markdown together, injecting code snippets based on special markers.

Automating tasks

Manually going through problems

In the early days of building this repo, if we needed to make a codebase-wide change, we'd go problem by problem, providing the relevant files to an LLM (usually in Cursor), and asking it to make a given change.6 This would take forever.

I tried asking the Cursor agent to "Do [TASK] for every problem in this chapter" (usually 10-20 problems), but this failed miserably. Agents back then were not able to keep track of task lists systematically. The agent would open a bunch of files without rhyme or reason, maybe make some changes, and after a while announce it's done.

They are much better now, but still not fully reliable.

Coordinating agents with external TODO lists

I had a breakthrough when I started using externally-managed TODO lists.

Before I start working with agents, I create a file with one line per problem:

problems/backtracking/thesaurusly/ | status: TODO | notes: |

problems/backtracking/to-be-or-not-to-be/ | status: TODO | notes: |

problems/backtracking/white-hat-hacker/ | status: TODO | notes: |

problems/binary_search/cctv-footage/ | status: TODO | notes: |

...

I can then give an agent a prompt that instructs it to process each problem in this file, from top to bottom, updating the status to OK / MISMATCH / UNSURE / ERROR, and adding notes accordingly.

To speed up the process and avoid running out of context on a single agent, I spawned a few agents in parallel, adding a different final line to the prompt for each one:

YOUR GOAL IS TO PROCESS ROWS 1 to 40.

YOUR GOAL IS TO PROCESS ROWS 41 to 80.

YOUR GOAL IS TO PROCESS ROWS 81 to 120.

YOUR GOAL IS TO PROCESS ROWS 121 to 160.

Here is an example of such a prompt.

This works surprisingly smoothly. The agents might miss a few rows, but it is easy for an agent to perform a final pass catching any remaining rows with a TODO status.

A refinement I added later: instead of all the agents seeing the same TODO file, I pre-partition it into multiple files and give each agent their own file. The less confusing you make it for them, the better.

Programmatically calling LLMs

The above process still requires manually spawning agents through Cursor's UI (or equivalent). When I translated all the Python solutions to Go, I wanted a more robust and automated solution.

To save cost and experiment, I ran a local LLM (DeepSeek-Coder-V2-Lite-Instruct-Q6_K7) on a local server (with llama.cpp).

Then, I vibe-coded a script that iterates through all the problem folders and, for each one:

- Reads the Python solution.

- Creates a prompt with the Python solution and a request to translate it to Go.

- Sends the prompt to the local LLM.

- Saves the output as

{problem_folder}/solution.go. - Runs the Go solution to verify it builds and passes the tests.

- Runs the parser to check if the injections match what the

writeup.mdexpects.

This script did not work well until I did the following improvements:

- Add retries: if Steps (5) or (6) fail, I call the LLM again, this time also providing the previous translation output and the error message. I gave it 3 attempts.

- Add few-shot prompting: I add in the prompt a couple of examples of successful translations, illustrating interesting edge cases.

- Examine a few outputs manually, identify common mistakes, and iterate on the prompt wording with specific instructions.

- The most important one: give up on local LLMs and buy OpenAI credits.

I ended up using ChatGPT-5.1, opting to avoid the coding-optimized variants. I have an intuition that coding-optimized models have a harder time following instructions that make code less idiomatic (like using nested functions) because it strongly goes against their training data and RL.

After the improvements, the translation went fairly well. Unlike the local models, ChatGPT-5.1 benefited a lot from the error messages in the retries.

Most problems were translated without hiccups, but a few that touched on topics where Python and Go diverge substantially (e.g., OOP), or that rely on unique injection patterns, still required postprocessing.

The translation was fast enough that I didn't bother parallelizing the LLM calls. The final cost was around $5.

This is the orchestrator script that calls a worker script for each problem.

Programmatically launching agents in parallel

The raw-LLM approach means you have to handle all the peripheral work, like reading and writing files, retries, etc.

We can use a more sophisticated tool, which is to spawn agents programmatically that have access to tool calls to do those things. The prompt can then be much higher level.

You can just say "Read problem.py and writeup.md" instead of concatenating those files into the prompt; or, "Run the code to ensure tests pass" instead of writing the retry logic yourself. In that sense, this approach is much simpler than the previous one.

The downsides are that agents are more expensive, slower, and hard to control.

In my case, I used Cursor's CLI for some of the refactors. Here is an example of a script that launches a Cursor agent for each problem. Since agents are much slower, it launches up to 14 in parallel.

Footnotes

-

As of writing, Go is not yet shown on the platform. ↩

-

The exception is when we need to import shared data structures like union-find. If we make a change to the union-find implementation, we want that to be reflected in all write-ups using it, so it shouldn't be duplicated. ↩

-

We have 1318 such insertions (an average of 4.6 per problem) because we also insert other things like data structures and recipes (a concept from the book). ↩

-

We have 540 such language-specific insertions (1.9 average). ↩

-

It used to be a hand-written script, but it has since become a vibe-coded monster as we added more features (as long as we don't see any unexpected diffs in the generated markdowns, it means it's still working). Incidentally, one of my first experiences being blown away by LLMs was writing this parser circa August 2024. Back then, I mostly used LLMs for tab autocompletion, as that's what I had seen at Google. I was thinking about the parsing logic for mapping top-level entities to line blocks by counting open brackets. Not too hard, but tedious and error-prone. That's when I installed Cursor and asked it to do it, and it did - as well or better than I would have - in an instant. ↩

-

Using cursor rules with an explanation of our injection logic and a style guide for each language was instrumental in getting the agent to follow our special rules. In addition, Cursor commands streamlined the process of using the same prompt across many problems. ↩

-

It's a good, recent model that fills most of my GPU's VRAM (RTX 4090, 24GB), while striking a good balance between the number of weights and quantization. ↩