Lifecycle of a CS research paper: my knight's tour paper

In math research, the way we arrive at a proof is nothing like how it is laid out in a paper at the end. The former is messy, full of false starts and dead ends. The latter is designed to be formal, concise, and neutral, devoid of any trace of personality of the authors.

While rigor is very important in a paper with theorems and proofs, it has the unfortunate side effect of being unrelatable. A common reaction is "How did they come up with that? I could never."

So, as someone who'd love to increase interest in theoretical CS research, I'll take one of my papers and try to make it more relatable by talking about everything that is not in it.

I'll choose a paper that was particularly fun: Taming the Knight's Tour: Minimizing Turns and Crossings (co-authored with Juan Jose Besa, Timothy Johnson, Martha C. Osegueda, and Parker Williams).

Background: the knight's tour problem

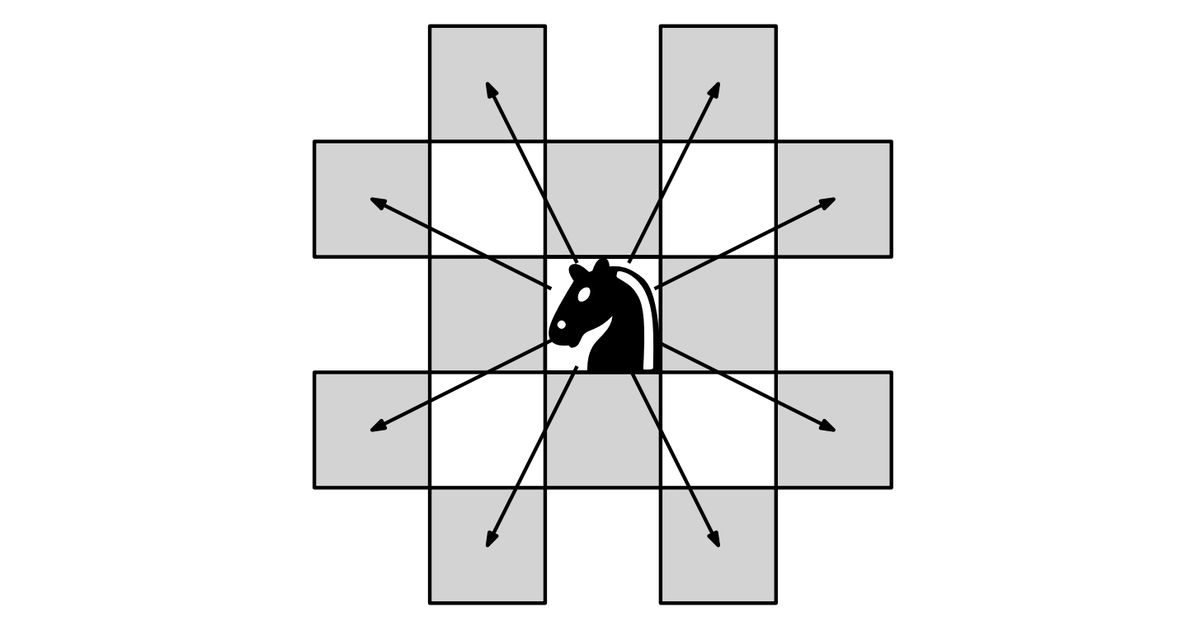

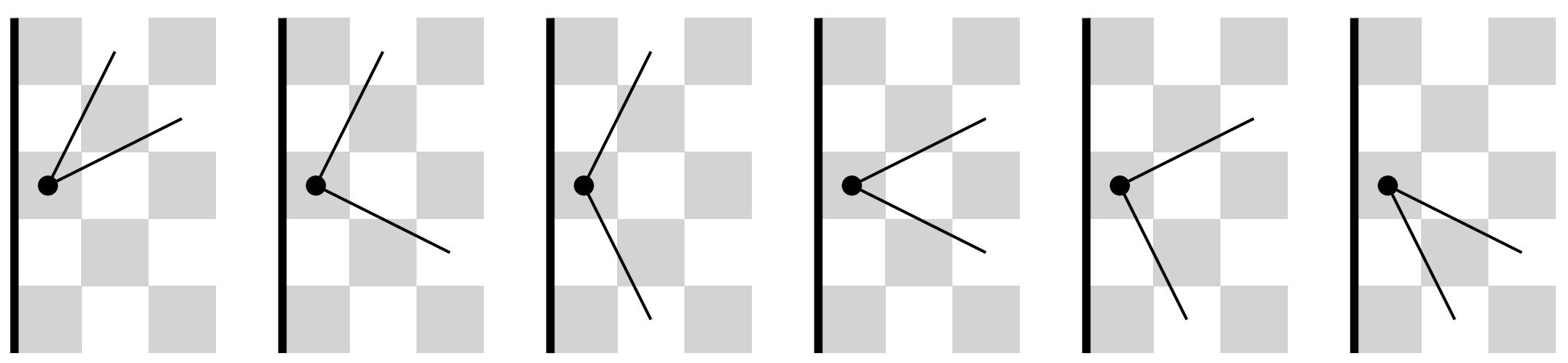

A knight is a chess piece that moves in an L-shape:

The traditional formulation of the knight's tour problem goes as follows:

A knight starts in any square of a chess board. The challenge is to visit every square, without repetition, using only knight moves, and return to the starting square. This puzzle becomes an interesting computational problem when generalized to n x n boards for any n.

Inception

The research group where I did my PhD had a fun little tradition: every Wednesday afternoon, we'd have a "tea time", where someone would propose a math riddle, and we'd try to solve it as a group while drinking tea and eating cookies.

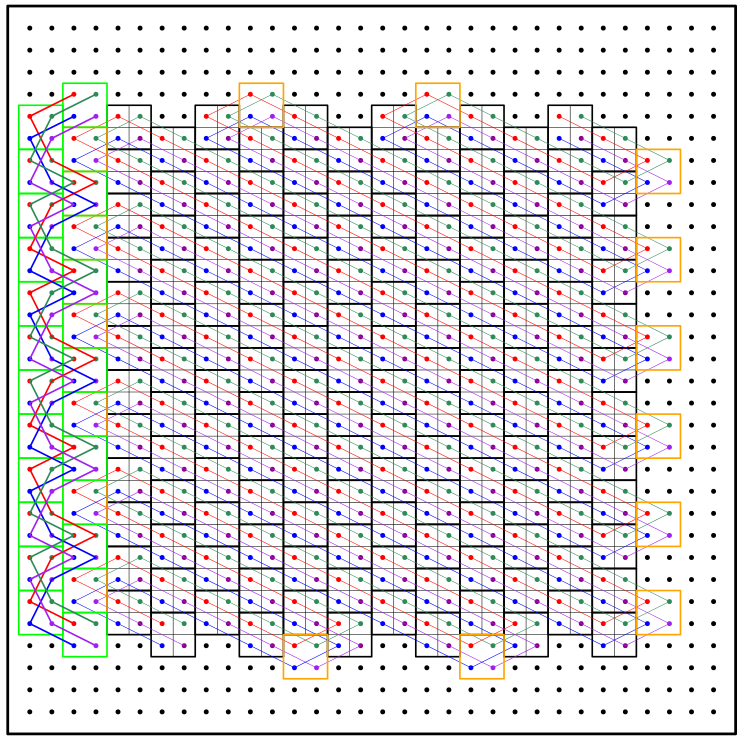

Our group does research on graph drawing (among other things), which is the study of graph embeddings in the plane. One of the central questions is about how to draw a graph in the plane with as few edge crossings as possible. With that in mind, I proposed the following problem during tea time:

"Look at a knight's tour on an 8x8 chessboard as a graph embedding, where the squares are nodes and the knight moves are edges. Can you find the tour that minimizes the number of crossings?"

This created a cute intersection between a classic riddle and one of the group's research interests.

The co-authors mentioned above were other PhD students from the group who came to tea time that week (except for Parker Williams, who will come into the picture later). This ended up being my only publication without any professor involved!

"Recreational mathematics is a gateway drug to hard math." - Erik Demaine (I believe).

Initial exploration

The first step is always the play around with the problem by hand to start building some intuitions around it. We started drawing tours on the whiteboard while trying to avoid crossings as much as possible.

The first observation was that the 8x8 board felt too small and constrained to avoid crossings, so we decided that it would be more interesting as a generalized problem in n x n boards for arbitrarily large n.

This put us more firmly in CS territory, where we care about how things scale. Instead of finding a specific solution, we were now looking for a generic way of constructing tours for any n x n board with a small number of crossings. That is, we were looking for an algorithm.

Upper and lower bounds

When looking at a new problem, it is always a good idea to establish

- (1) how well do existing algorithms do on the problem, and

- (2) what is the absolute best we could hope for.

The former sets a baseline for what we have to beat to have something interesting at all; it gives us an upper bound on the number of crossings in the optimal tour. The latter establishes a lower bound.

Sometimes, you find that the upper bound and the lower bound match, in which case there is no room for progress and the project is essentially dead.

When thinking about these bounds, we realized that it'd be easier, while still interesting, to minimize turns instead of crossings. A "turn" is a cell where the knight changes directions. Turns are easier to work with because a cell is either a turn or it is not, while an edge can be involved in multiple crossings. So, we decided to focus on minimizing turns.

As you can see, we have already reframed the problem twice. Trying to find the most interesting (but still doable) questions is an organic part of research.

Working with turns instead of crossings gave us a trivial lower bound: every cell along the edge of the board must be a turn, so we have at least 4n - 4 turns on an n x n board.

To establish an upper bound, we looked at how existing algorithms do on the metric of minimizing turns. We found that there are only two main kinds of knight's tour algorithms:

- Backtracking algorithms with heuristics like Warnsdorf's rule. The idea is to construct a tour step by step, always going to the most promising next move (according to the rule), and backtrack if we get stuck. These algorithms, while very effective for 8x8 boards, quickly reveal their exponential nature for larger boards.

- Divide-and-conquer algorithms, which split the board into four quadrants, 'solve' each quadrant recursively down to, e.g., 8x8 boards, and then change some of the boundary moves to concatenate the different bits together.

Backtracking algorithms are inherently uninteresting because they don't scale and don't have structure that can be analyzed.

The divide-and-conquer algorithms, however, allowed us to establish an upper bound: on an n x n board, the board ends up divided into about ~n^2/64 "tiles", assuming that the base case is 8x8. Each of these tiles must have at least one turn, so the tours from these divide-and-conquer algorithms have at least O(n^2/64) = O(n^2) turns.

This leaves us with a very interesting gap between the O(n^2) upper bound and the O(n) lower bound.

At the time, after playing around with the problem and looking at existing

backtracking and divide-and-conquer solutions, I had a strong intuition that

O(n^2) was the best possible number of turns. I had an even stronger

intuition that O(n) turns was impossible. At best, I thought we could find

something in between, like O(n^1.5) turns.

First approach: generalizing from small boards

A common problem-solving technique is to look at the solution for small inputs, and try to extrapolate the pattern to larger inputs. In our case, that means brute-forcing the problem for small boards, and see what the optimal solutions look like there. Maybe, that would show us some emergent structure that we could use to construct larger solutions.

However, even for small boards, it is far from easy to find the optimal tour. To that end, Tim encoded the problem in the Z3 theorem solver, a general optimization tool, to find the tour with the least number of turns.

This was a laughable failure: the solver took about 2 hours to run for 6x6 boards (the smallest size with a tour), and it never finished running for the next smallest board with a tour, the 8x8 one.

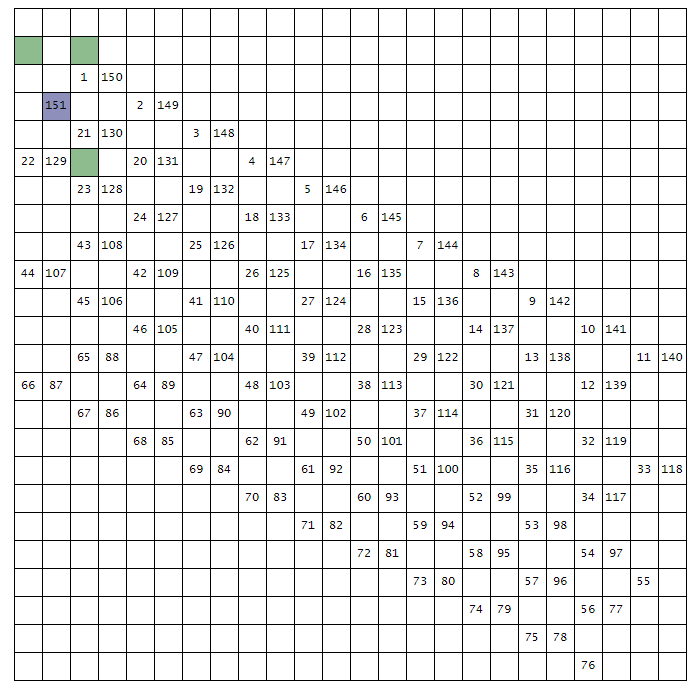

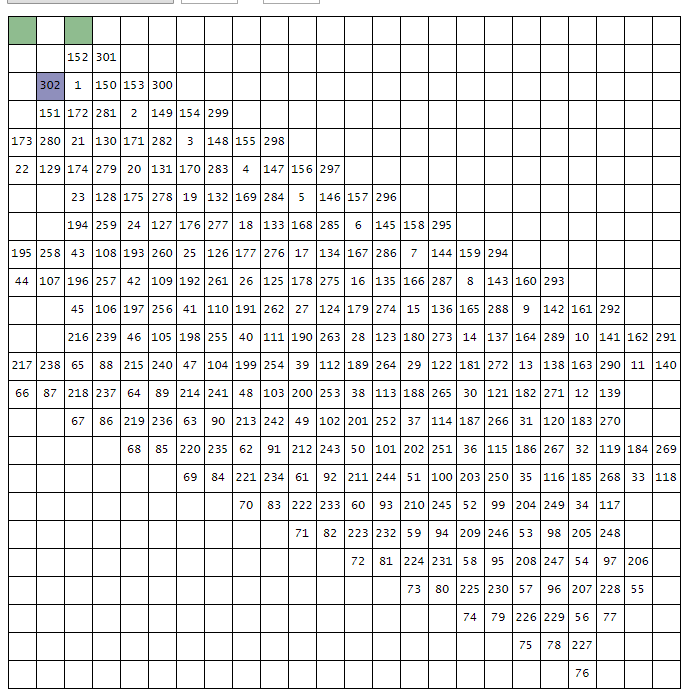

Here is the optimal tour for 6x6 boards:

0 11 20 29 2 9

21 28 1 10 19 30

12 35 22 31 8 3

27 32 7 16 23 18

6 13 34 25 4 15

33 26 5 14 17 24

Looking at the "optimal" tour for 6x6 boards gave absolutely no insight: due to the small size, almost every square was a turn. The optimal tour has a total of 32 turns in 36 squares. Face palm moment.

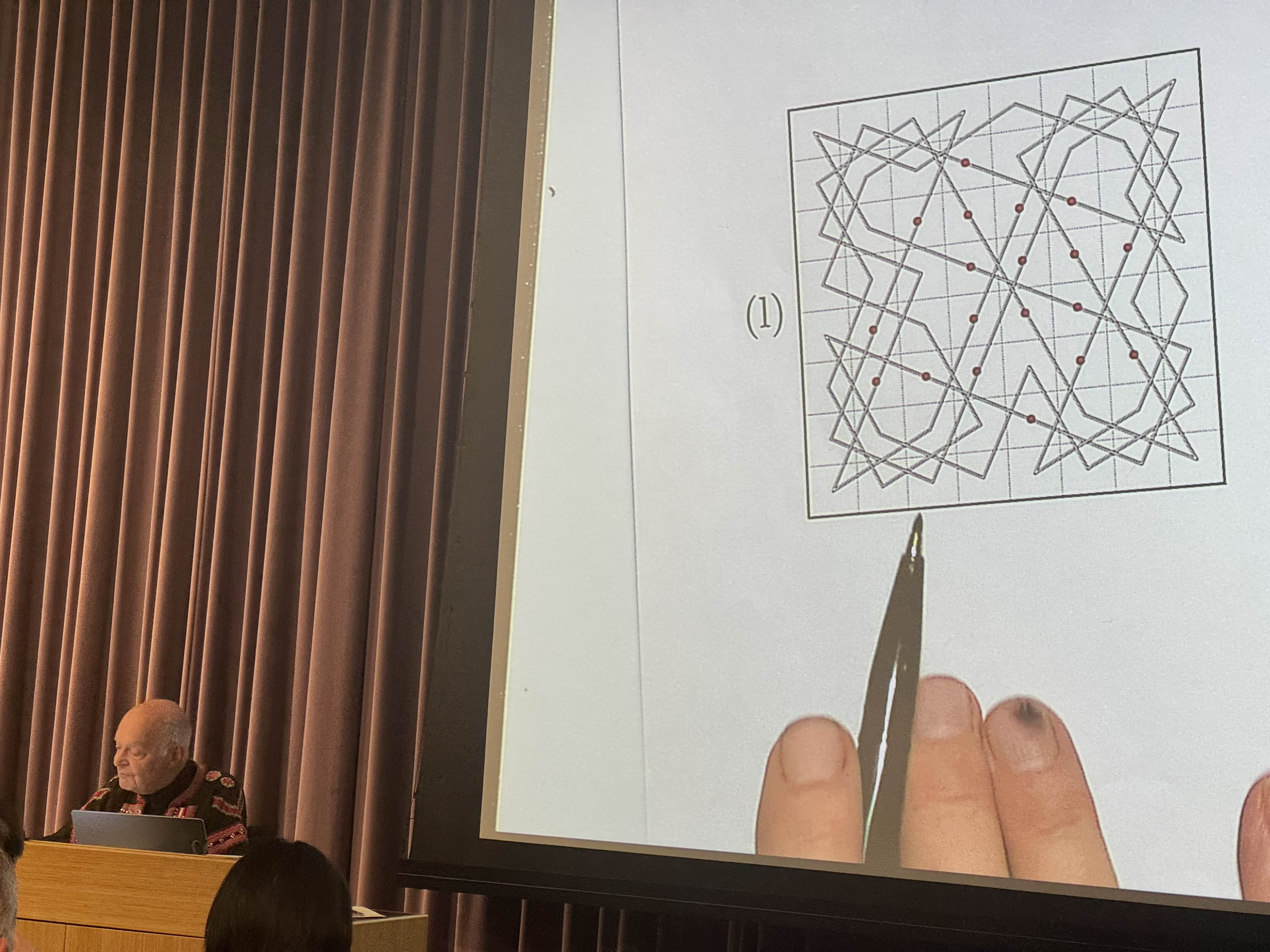

Funnily enough, there is one person who'd later become interested in the problem of finding the 8x8 tour with the fewest turns: Donald Knuth. And unlike us, he succeeded. He presented the tour in his 29th Christmas Lecture (2025), Adventures with Knight's Tours, which I attended and where I snapped a picture of it:

I shared some thoughts on the lecture and how it overlaps with our work in this tweet.

Second approach: aim for the sky

The next approach we tried was to start from the lower bound:

"If a tour with O(n) turns existed, what would it look like? And, if it is not possible, what exactly is the obstacle?"

Understanding what, exactly, makes a problem hard, can lead to insights for how to address it.

So, we asked, "what if none of the inner squares had a turns?" What if all the turns were along the edges?"

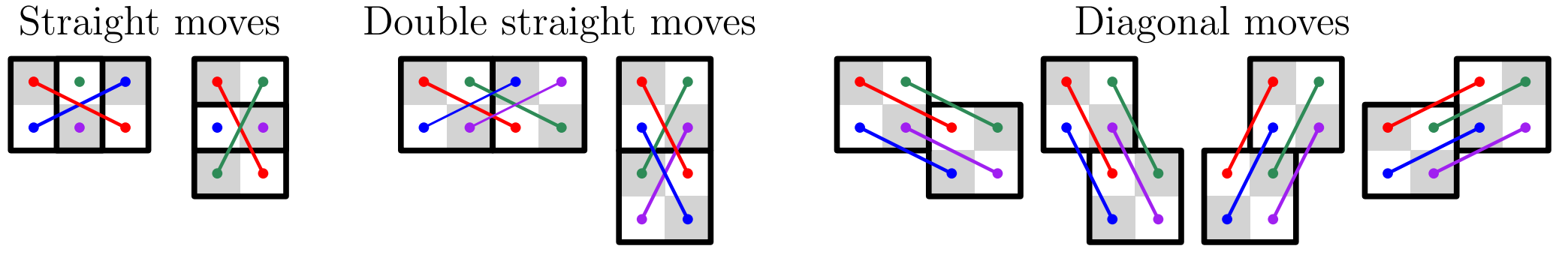

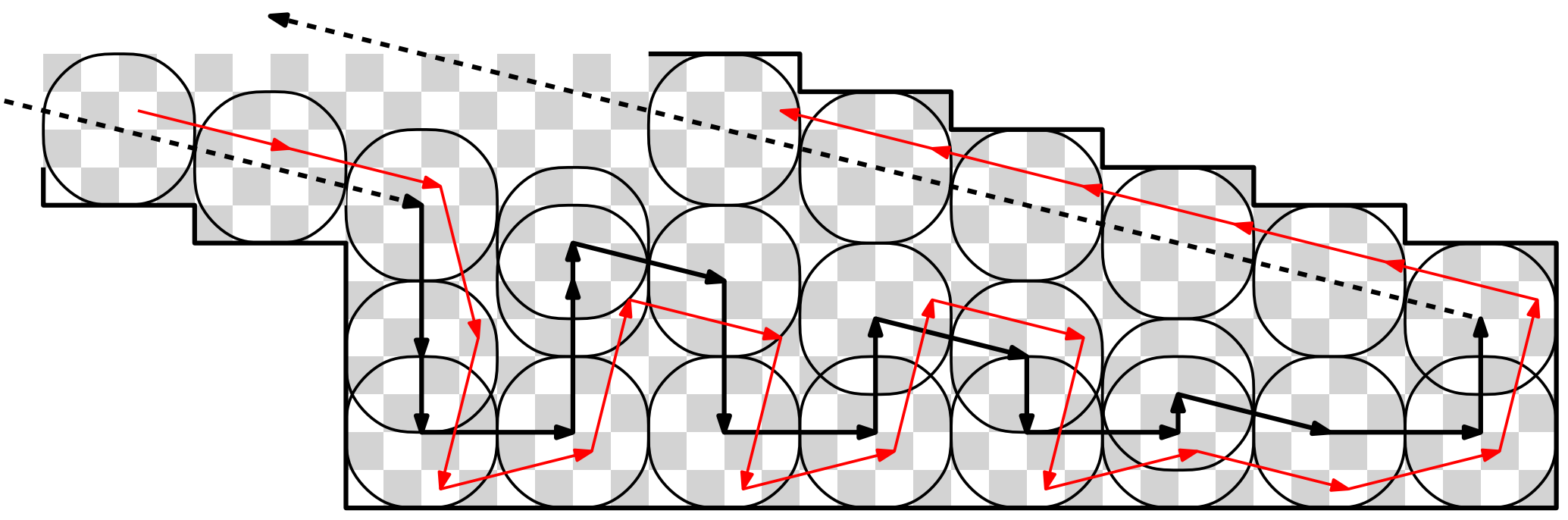

We started drawing a tour that would only turn near the edges, like this, knowing that it would be practically impossible to actually finish it:

We learned that we could cover a compact chunk of the board this way, leaving only the edges to figure out later:

Now, the "only" thing that was left to get a tour with O(n) turns was completing the edges of the board. While obviously hard, it didn't seem outright impossible.

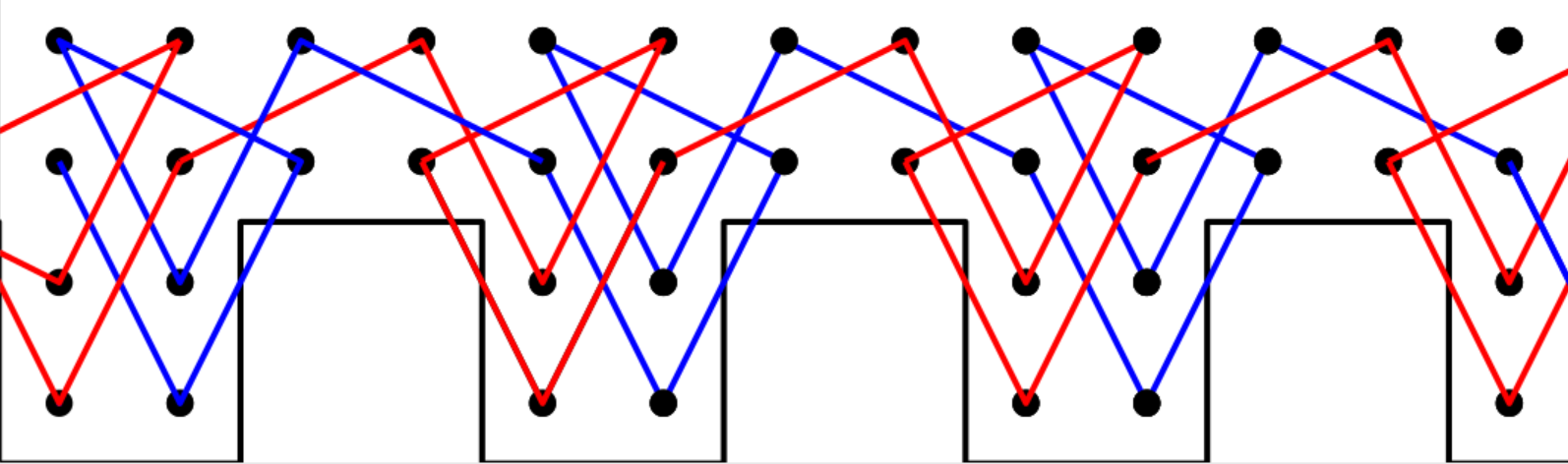

We started looking at ways of covering a narrow strip, and we found constructions like this, which consists of two separate path segments (red and blue):

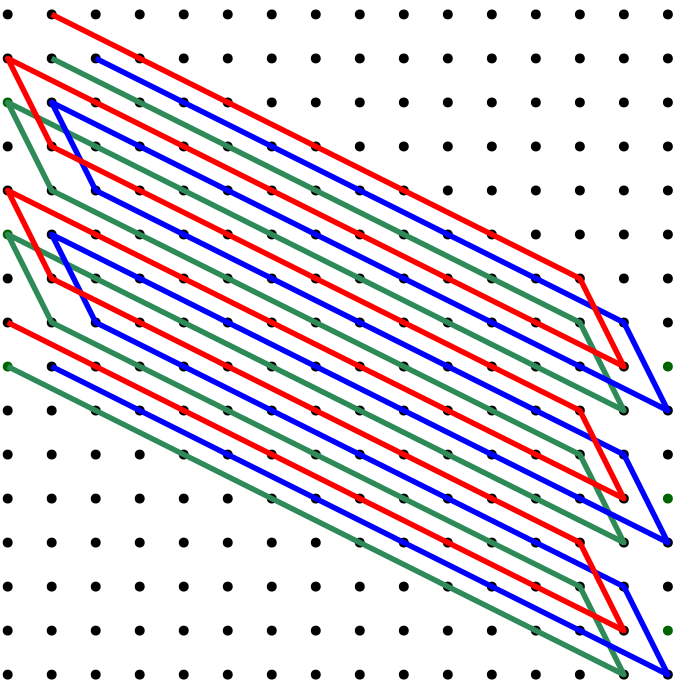

Since the previous image shows a way of covering an edge pattern with two path segments, we started exploring the idea of covering the main body of the board with multiple path segments as well. Here's an example with 3 path segments:

A happy idea

At this point, we still didn't have anything concrete, but we kept exploring patterns.

We found that using 4 path segments seemed to fill the board with a pretty regular shape:

It was looking at this that we hit on the key abstraction that made the whole project fall into place:

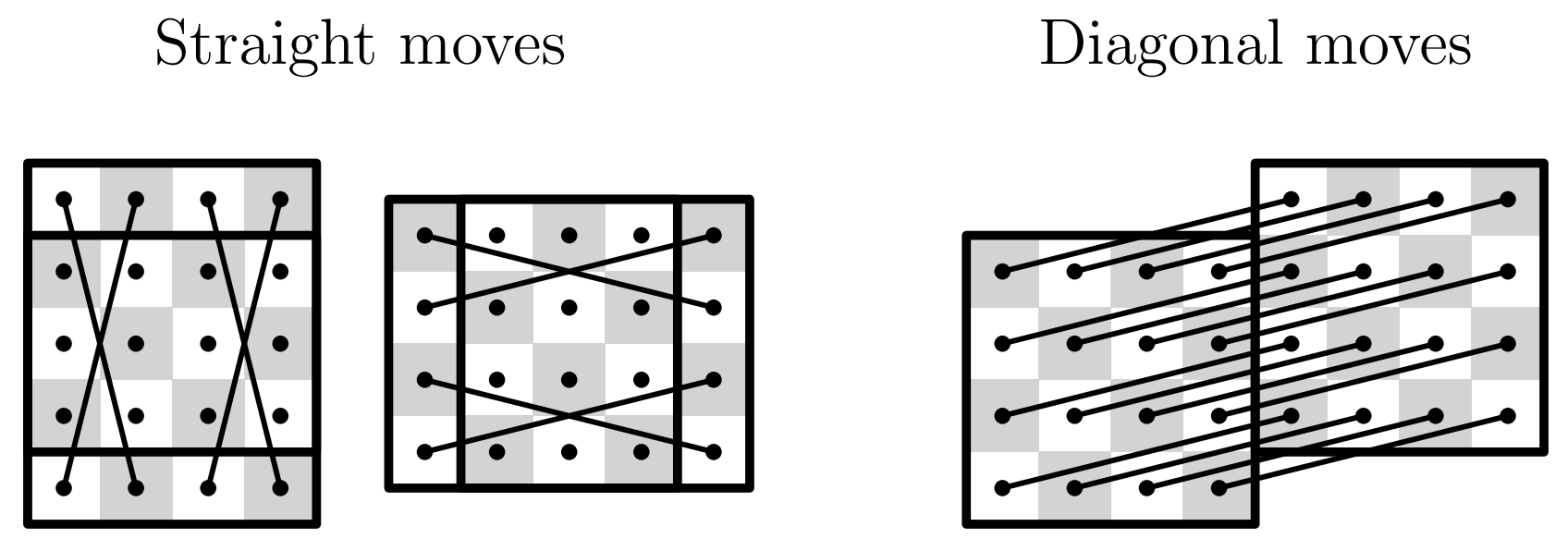

A 2x2 formation of knights moves kind of like a king. That is, four knights

can make straight moves (up, down, left, right) or diagonal moves without

leaving any gaps in between.

What makes the knight case hard compared to a king is that, when it moves, it leaves "gaps" that need to be filled later. But this formation solves this problem!

We now had a clear direction: instead of traversing the board with a single knight, we'd traverse it with a formation of four knights. Then, somewhere, like in a corner of the board, we'd reserve a special region to tie together the four knights into a single path.

Obviously, we still need to work out the "tie together" part, but that seemed very doable.

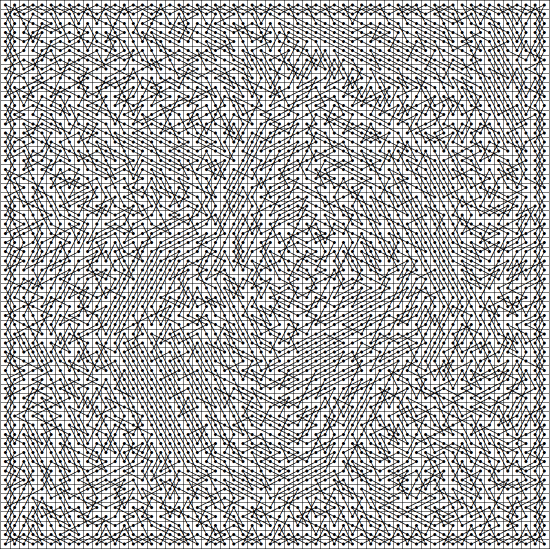

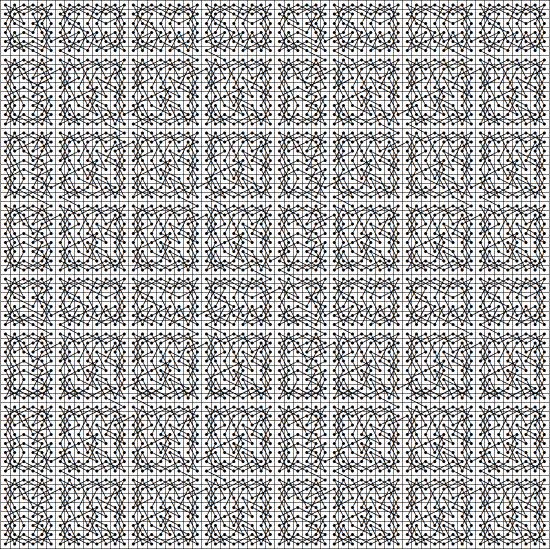

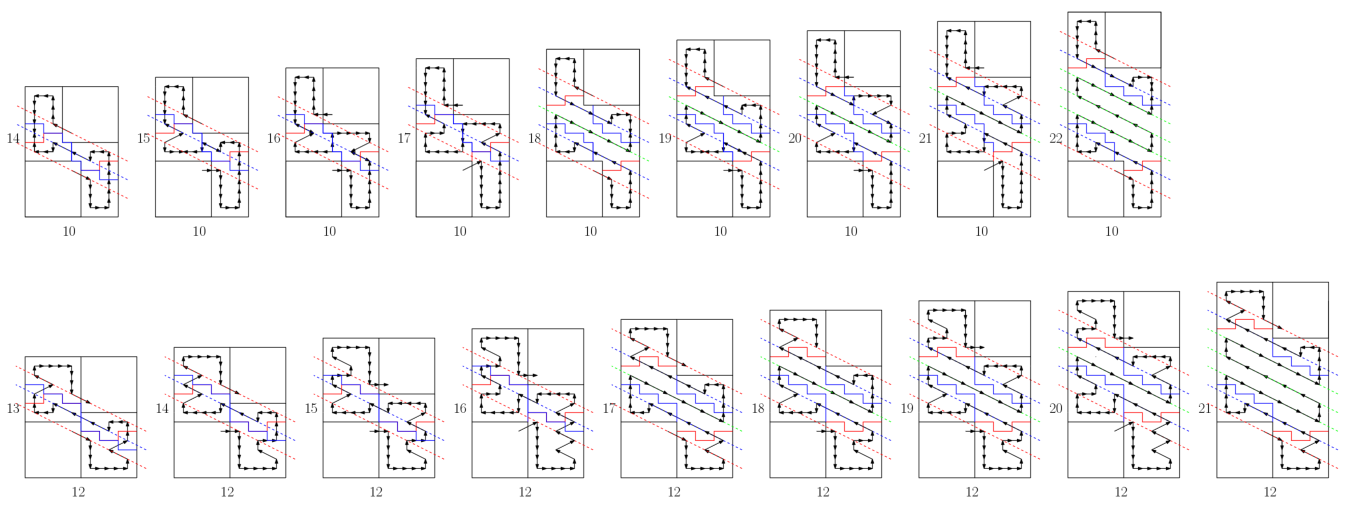

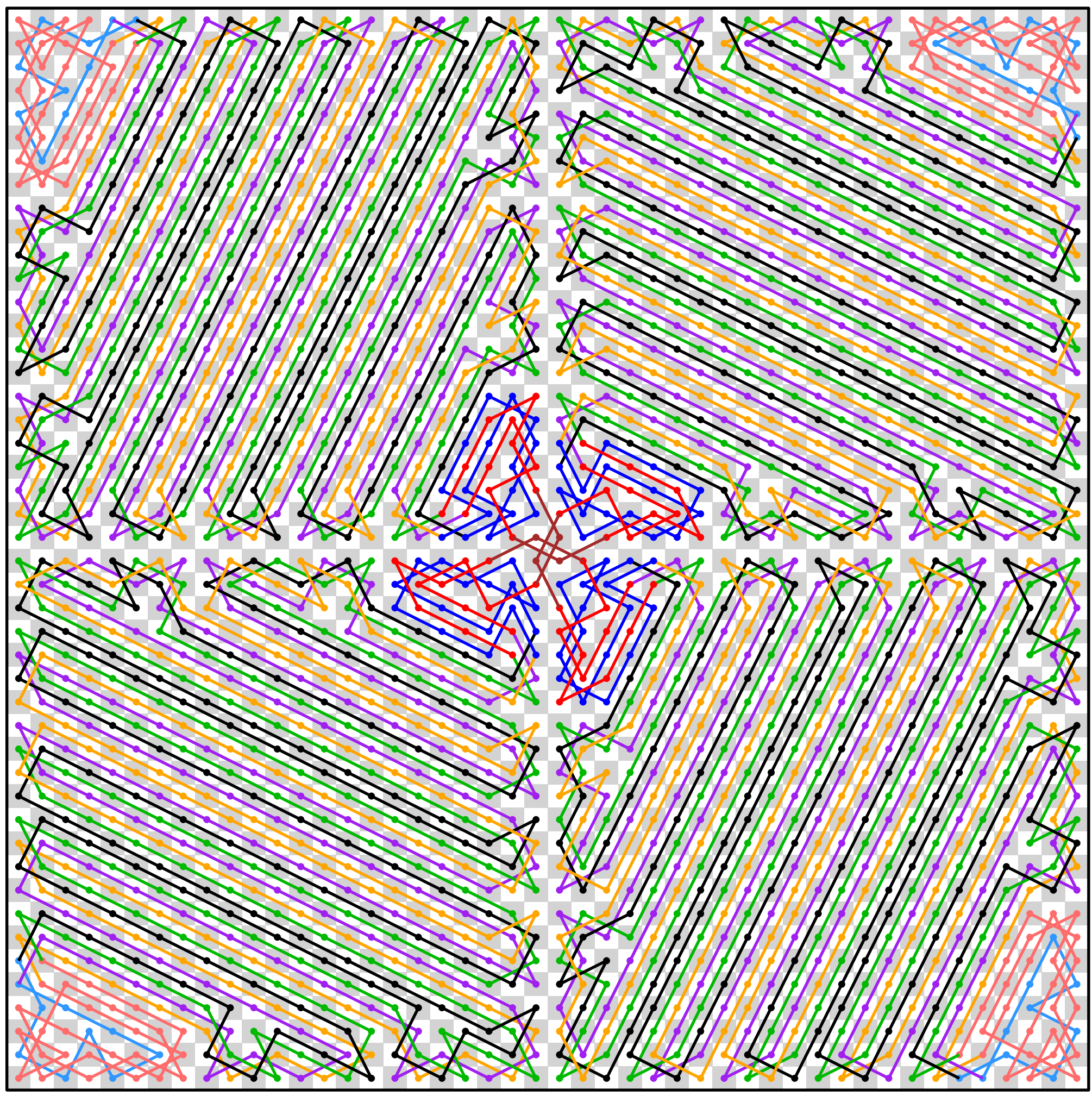

Unlike the divide-and-conquer approaches, this new approach is actually great for minimizing turns. Straight formation moves (up, down, left, right) introduce turns, so they are no good, but consecutive diagonal moves in the same direction do not. Thus, our approach to minimize turns consisted on maximizing long sequences of diagonal moves, resulting in this zig-zag pattern across the board:

And this can be tied together into a single tour by filling in the corners carefully:

Figuring out the corners

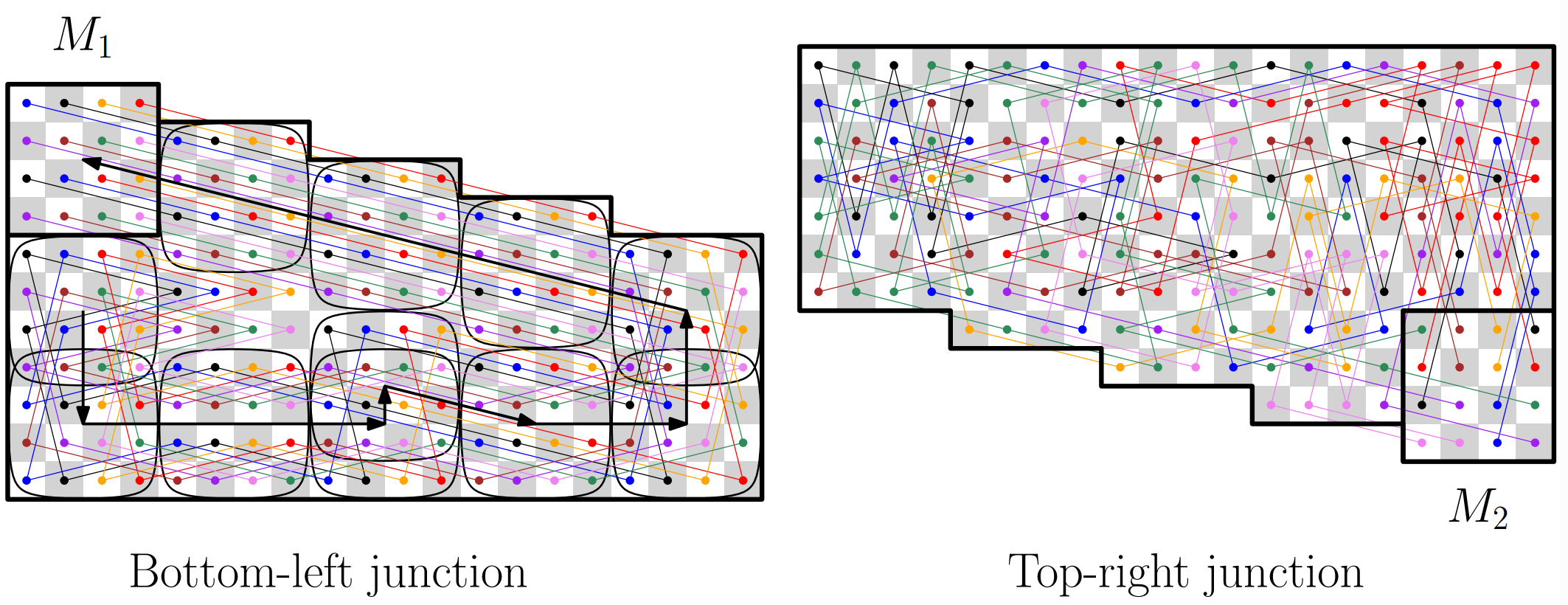

One challenge is that different board dimensions require different corner patterns, so we had to put some attention to detail when proving that the construction works for all dimensions.

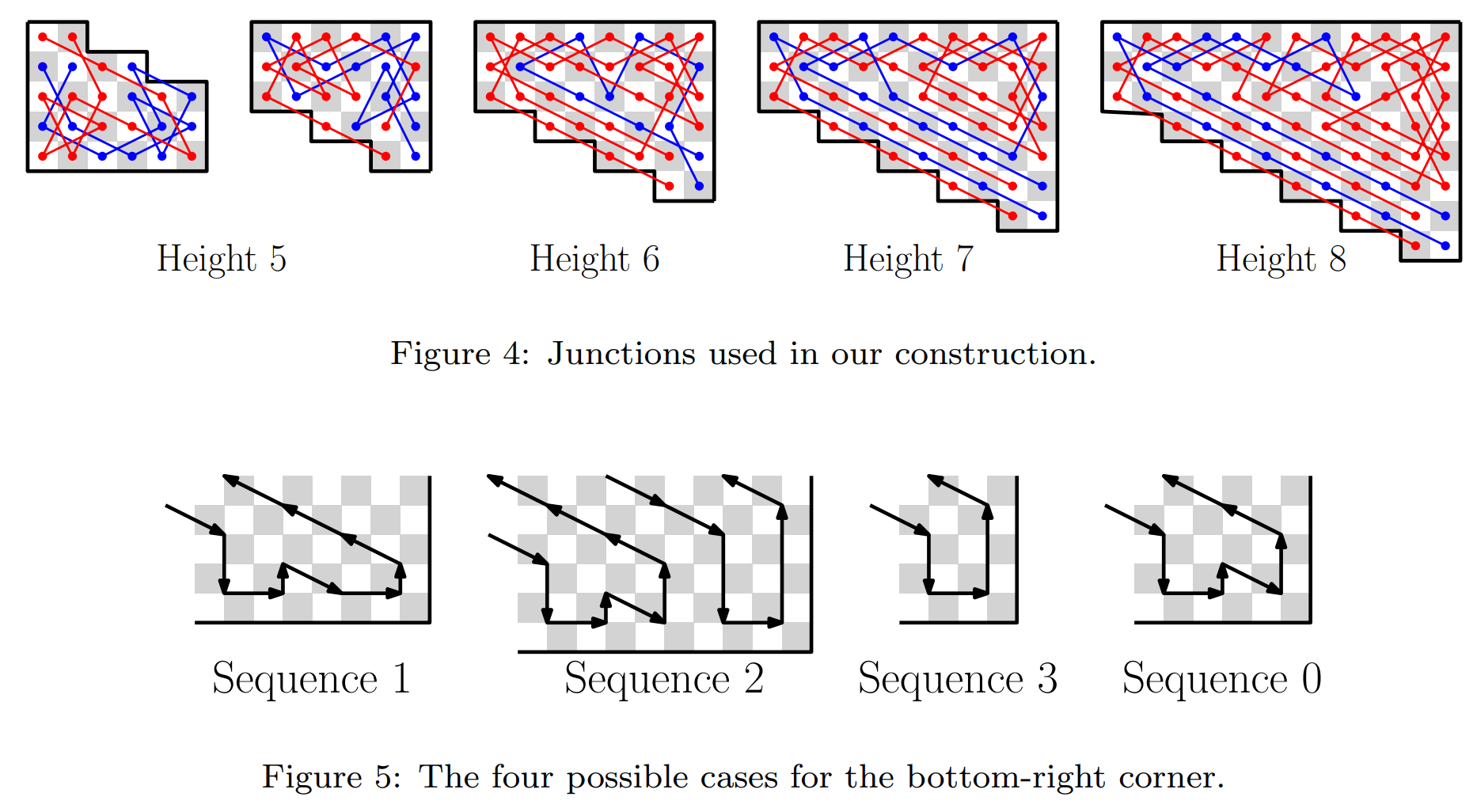

Eventually, we showed that we can handle any board dimensions with some combinations of the following corner patterns:

You can try different dimensions in our interactive demo here: nmamano.github.io/MinCrossingsKnightsTour.

This is formalized as Algorithm 1 in the paper (along with a formal proof that it always forms a complete tour).

With it, we now had our holy grail: a tour with O(n) turns and crossings, since all turns and crossings happen along the edges, which contain O(n) cells. This matches our lower bound, at least asymptotically, defeating my intuition that it was impossible.

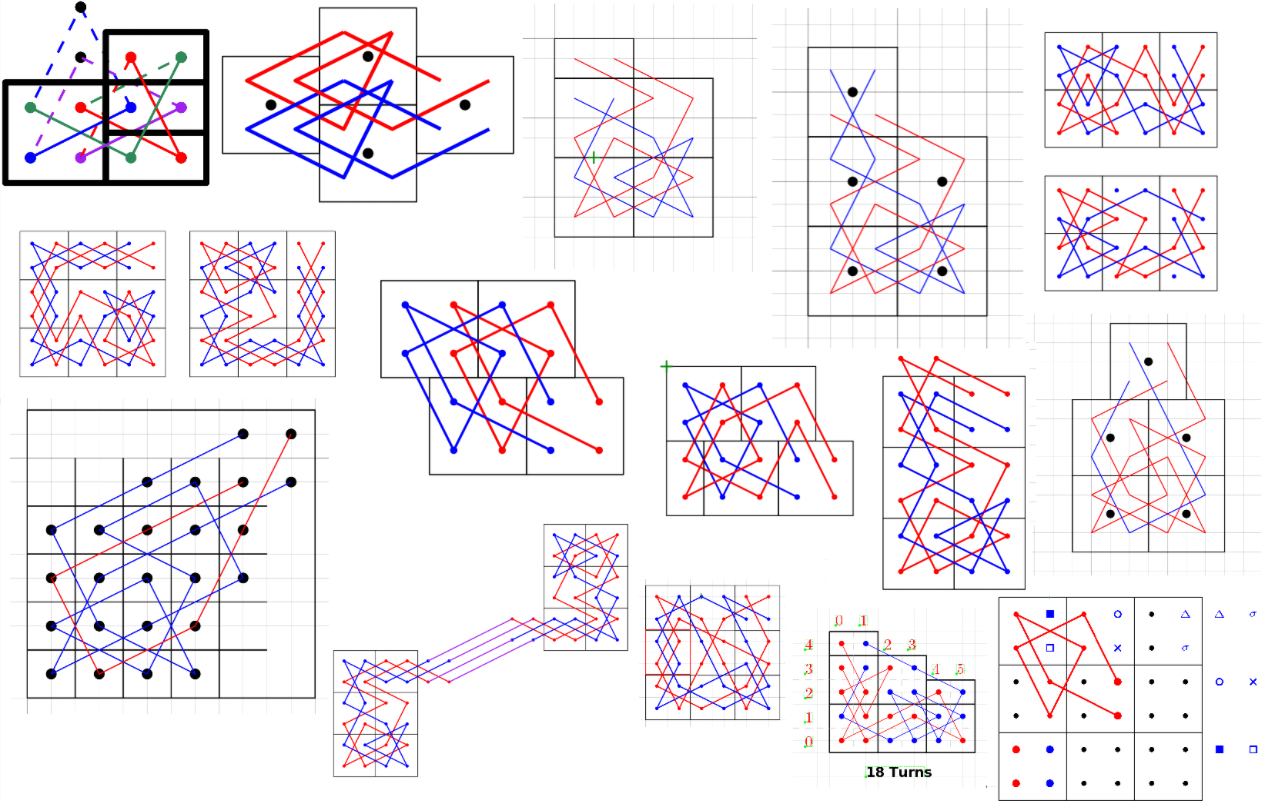

Now, if you just read the paper, you'd think that plugging in the right corners was straightforward. And, to be clear, finding corners that work is not too hard. But we still spent a lot of time figuring out the cleanest way to handle them. Here is a collage of sketches we shared in the project's group chat--and it's not all of them:

I could make another collage for how to handle the bottom-right and top-left corners, which we covered with formation moves. For instance, here is some case analysis we did for how to handle these corners for different rectangular board dimensions:

This case analysis used "square" corners in the bottom-left and top-right corners, which we ended up not using in the paper.

Like the tip of an iceberg, a paper hides most of the work that goes into making it.

Generalizations

When presenting a new idea in a paper, it is a good idea to ask "what other problems can be solved with this idea? can it be generalized to other problems?" This is a good way to make your paper stronger and increase your chances of getting through peer review.

In our case, it seemed clear that our idea should be able to handle rectangular boards, so, when we formalized the algorithm, we made it in a way that works for any dimensions where a tour exists (i.e., where the dimensions are not too small and at least one dimension is even).

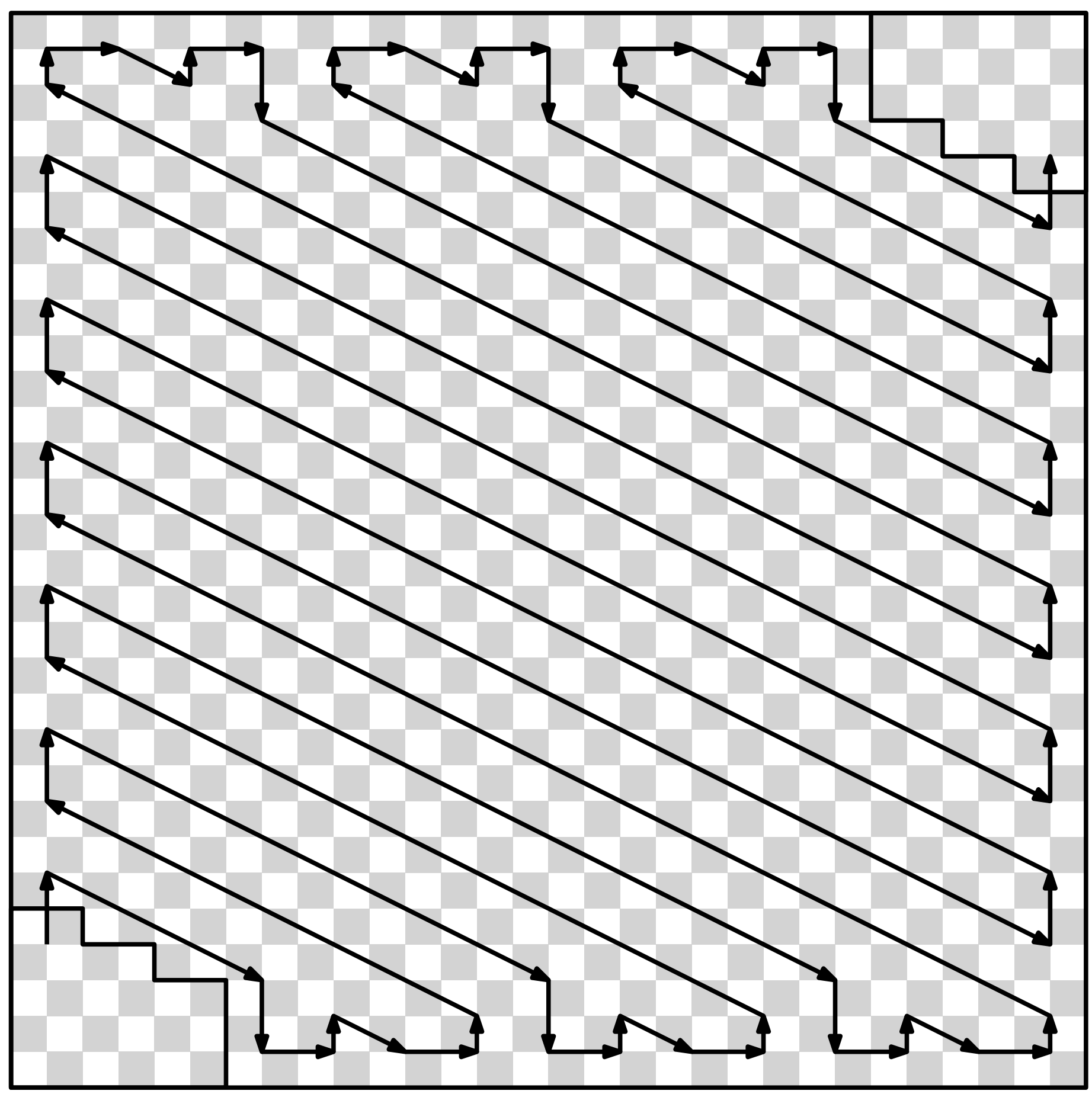

But we didn't stop at rectangular boards. Since we had to go through the literature on the knight's tour problem to make sure our idea was new, as we did, we looked at all the variants that people have addressed in the past. Then, we used our knight formation idea to tackle those as well:

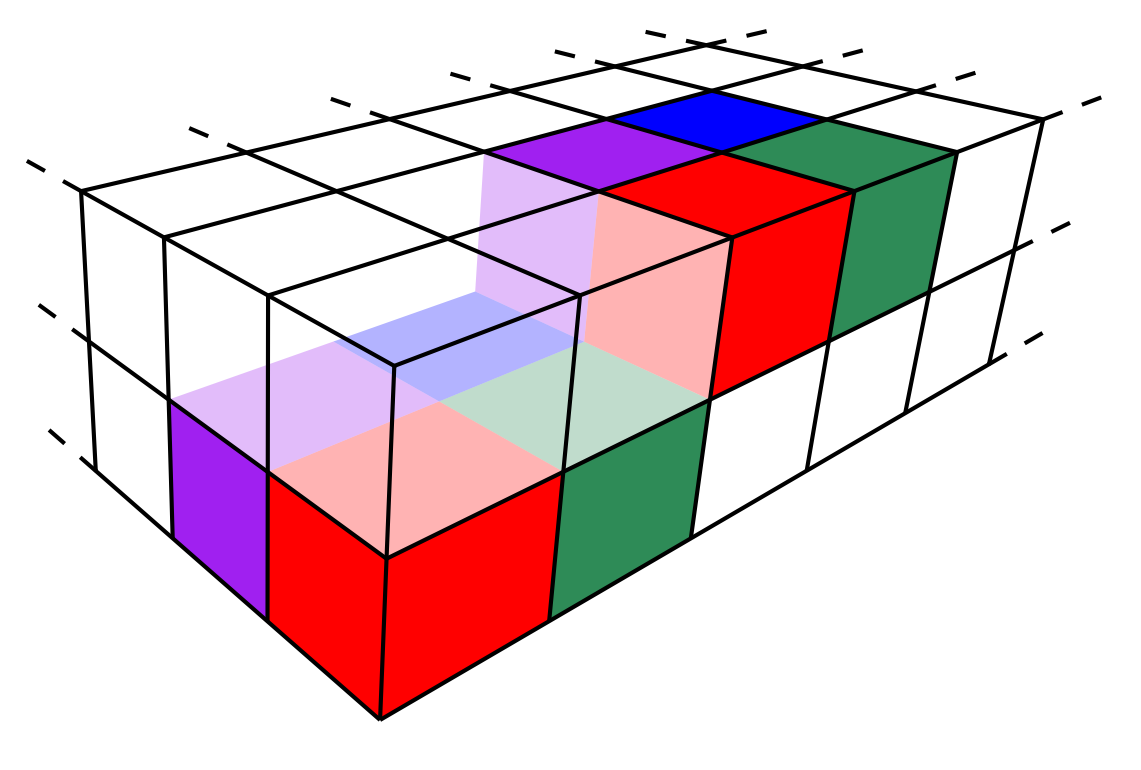

- Tours on boards with three and higher dimensions. Here you can see the 4-knight formation moving from one layer of a 3D board to the next:

(This figure sent me on a side quest to figure out perspective drawing in a 2D drawing editor).

- Tours that are symmetric under 90 degree rotations. We did this by stitching together four copies of our tour:

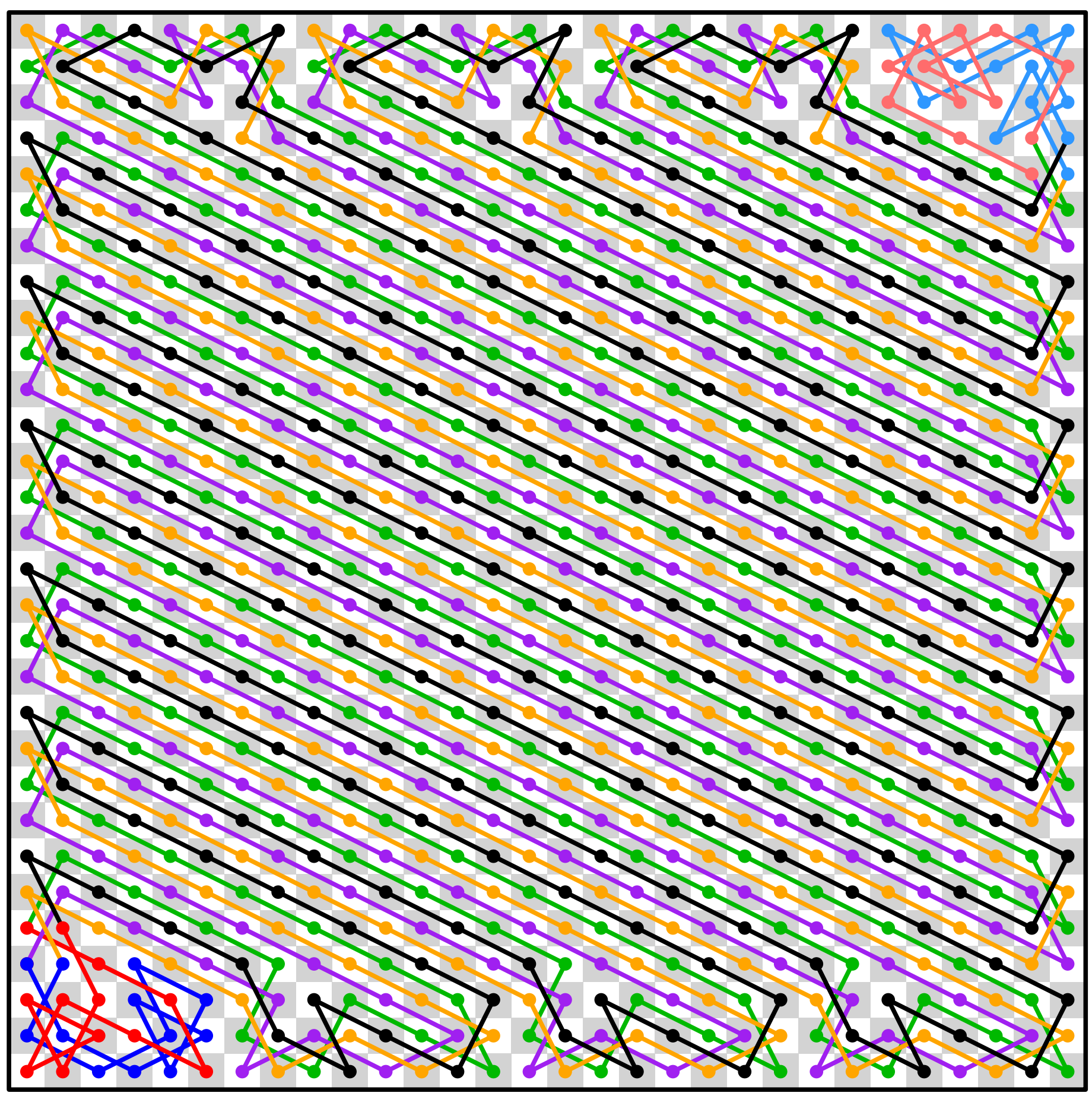

- Tours for "giraffes", which move one square in one direction and 4 in the other. This one is funny because it involves a formation of 16 giraffes:

Transition from one diagonal to the next with 16 giraffes is kind of an ordeal:

And making sure that the corners tied the 16 giraffes together into a single path was impossible to do by hand. I coded a backtracking algorithm to crack it.

Behold, the ultimate monster:

Anyway, enough horsing around...

We essentially covered the main variations discussed in the literature. In each case, we mostly had to make tweaks about how to handle corners, but the main idea held well. To me, this suggests that our technique should be the go-to approach for the knight's tour problem even when you don't care about turns and crossings, but I may be biased ;)

Besides these variations, to further strengthen our paper, we also showed that our algorithm was not only efficient (running in linear time) but also highly parallelizable.

Approximation ratios

As we mentioned, the number of turns on an nxn board, O(n), is asymptotically optimal. That is, our tour is within a constant factor of the optimal number of turns.

However, we can refine that: what is the exact number? and how close is that to the optimal number?

The first question is straightforward: we calculate how many zig-zags the formation makes as a function of n, and then multiply that by the number of turns made by the formation each time it transitions to the next diagonal. In total, we get 9.25n + C turns, where C is some small constant.

The second question is much more difficult. To know how far we are from the optimal number, we would need the optimal tour, which we obviously don't have. Instead, if we can find some lower bound on the number of turns, then the ratio between the lower bound and our count gives us an approximation ratio of how far off we are from the optimal number in the worst case.

We already discussed a trivial lower bound: every cell along the edge of the board must be a turn, so we have at least 4n - 4 turns.

However, the higher we can take it, the better our approximation ratio will look.

We were able to prove a lower bound of 5.99n. That is, no matter the approach, there must be at least 5.99n turns in any knight's tour. (The exact statement is: for any ε > 0, there exists an n0 such that, for all n > n0, a knight's tour on an nxn board has at least (6 - ε)n turns.)

The proof is a bit convoluted, but it comes from a simple intuition (as is often the case...). Take all ~4n edge cells. Each one has two "legs": sequences of aligned moves coming out of it. The legs end when they either (a) reach another edge of the board, or (b) run into something that prevents them from reaching it. The idea is that the ~8n legs running across the board make the board too crowded and eventually some of them "crash" into each other, creating new turns that are not at edge cells. We show that there must be at least ~2n "crashes", bringing the lower bound up to ~6n.

I won't get into why (you can see the paper), but I found it pretty unexpected that the proof involves a fractal, so I'll just show the fractal here out of context:

Combining the upper and lower bounds, we get an approximation ratio of ~9.25/6. A pretty small gap!

So, what do I think is the actual optimal number? I'm really not sure, but I think it will be easier to raise the lower bound than to lower the upper bound.

Eventually, we circled back to the original problem of minimizing crossings, and we were able to show an approximation ratio of ~3 in that case. Our construction has ~12n crossings, and the best lower bound we were able to show is ~4n. (This lower bound seems like low hanging fruit for improvement, if anyone is looking for a problem to work on!)

Unexpected help

One day, I received the most random (and delightful) of emails: a student from a class I TA'd, Parker Williams, sent me an improvement to our approximation ratio out of nowhere. We had never discussed collaborating on this.

The email read:

Hi Nil,

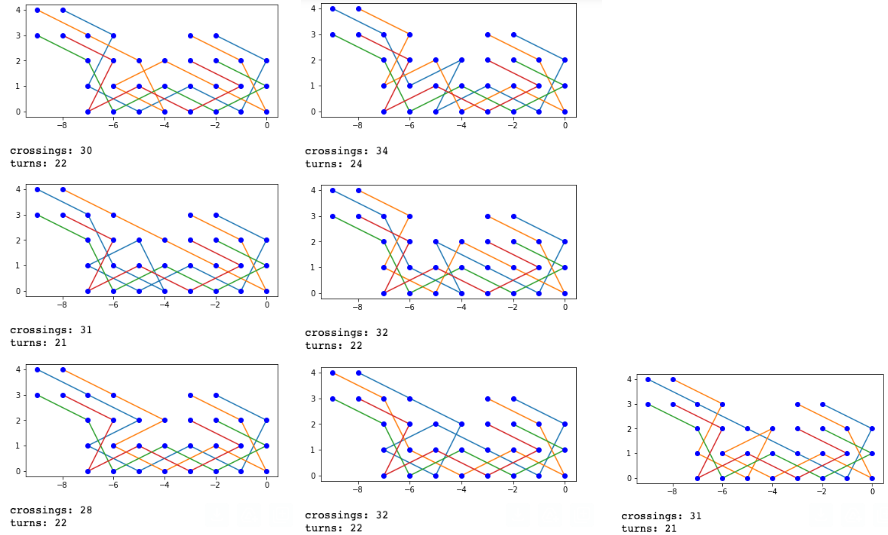

I had a look at the heel in the open problems doc and I couldn't help myself, here are all possible tours for the "small heel" (there are possible improvements for both turns and crossings!) the one used in the paper is the fourth one down:

I found this list by searching the problem space exhaustively, I was expecting it to take too long and that maybe a greedy/DP type algorithm would be necessary but the whole search actually finished in less than a second in python on a laptop.

[...]

Are any of the small heel findings valuable? I understand it's a very marginal improvement in upper bound [...].

Yes, yes, they are! Parker's optimized diagonal transitions improved our upper bounds from ~9.5n turns and ~13n crossings to ~9.25n turns and ~12n crossings (as mentioned above), tightening the approximation ratios a bit further.

By that point, we had already published the paper in a conference called FUN (short for "Fun with algorithms"), but we had been invited to publish a journal version in TCS, so we added Parker's results to the journal version and added him as a co-author.

Still one of my favorite emails I've ever received.

Conclusion

I hope this post helped demystify CS theory research a bit--even if it is for a silly puzzle that originated at tea time. I may summarize it as: it's not as hard as it seems, but it is more work than it seems. So, enjoying the process and having fun is probably more important than being a genius.

Want to leave a comment? You can post under the linkedin post or the X post.