A topology/geometry puzzle

In this post, we'll study what kind of solids (3D shapes) we can get by taking a solid and merging two of its faces.

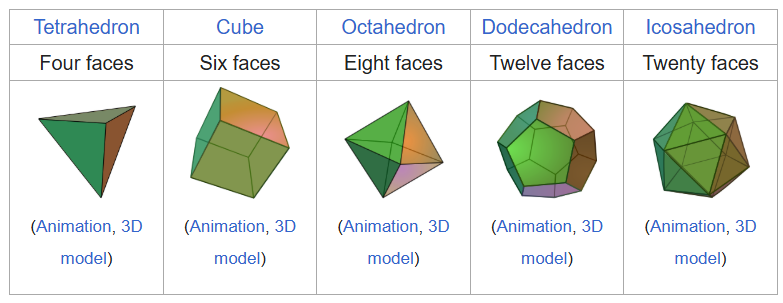

The goal of this project is to characterize every solid that can be created starting from a platonic solid (what that means, precisely, will be clear later). I'm ~40% of the way there.

Disclaimer: I have not done any literature review for this post (I did enough of that in grad school!) so it is very likely that this space has already been explored. This is just for fun. If you happen to know of any related work, please let me know!

Rules

Let's formalize what operations are valid. I'll start with (filled) 2D shapes, which are easier to visualize.

Morphing

In topology, a cube, a sphere, and a sock are all the same thing because they can be deformed into one another without cutting or gluing. We say they are homeomorphic.

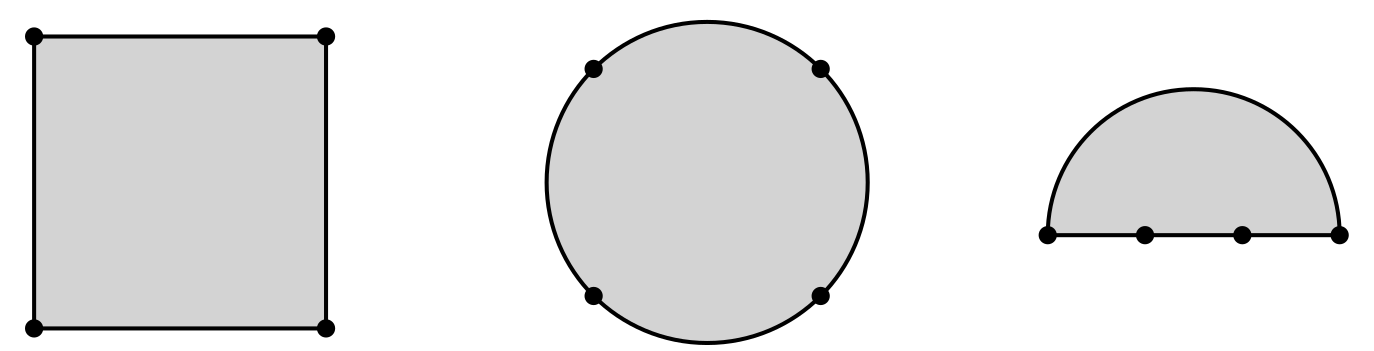

We have a similar concept here, but we also account for vertices and edges. These three 2D shapes are homeomorphic because they all have a face with 4 vertices and edges:

In contrast, a square is not homeomorphic with a triangle, because, even though both can be deformed into the same 'shape', the vertices and edges do not match.

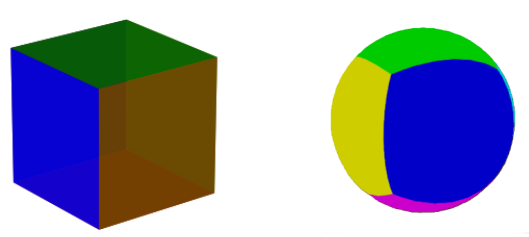

The same applies to 3D solids, where two solids are homeomorphic if they can be deformed into one another without cutting or gluing, with matching faces, edges, and vertices. These two shapes are homeomorphic:

Merging

This is the only operation we can do which transforms a 2D shape (or 3D solid) into another shape/solid that is not homeomorphic to the original one. I'll start with 2D.

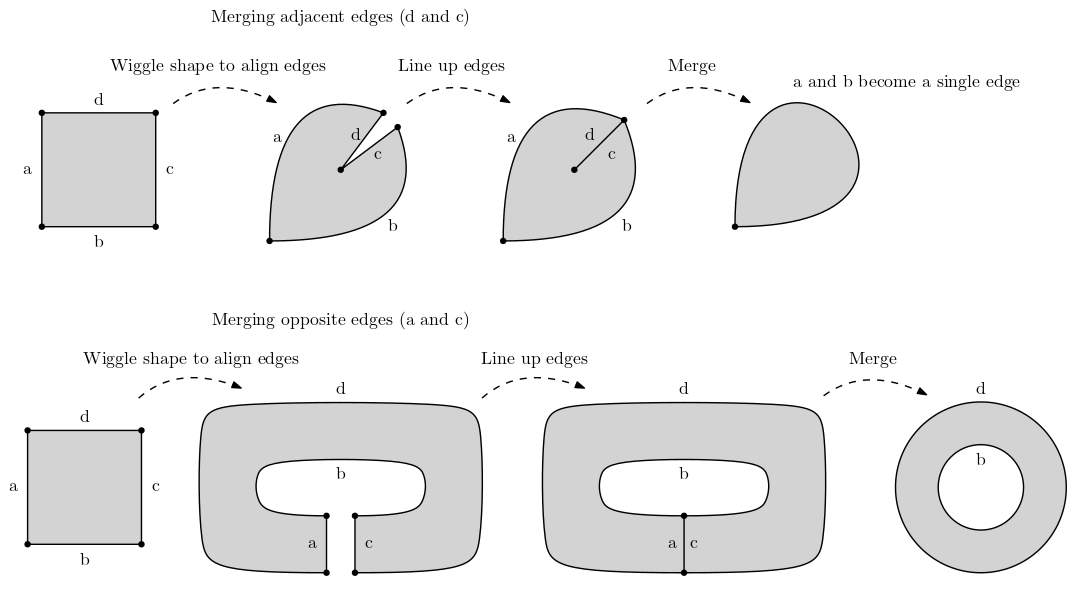

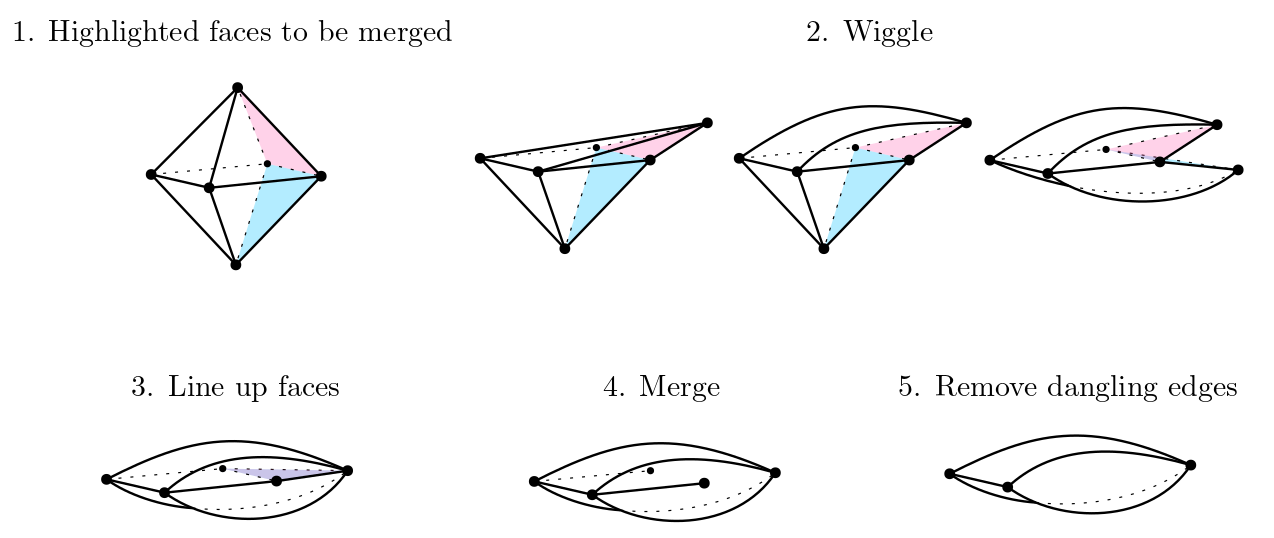

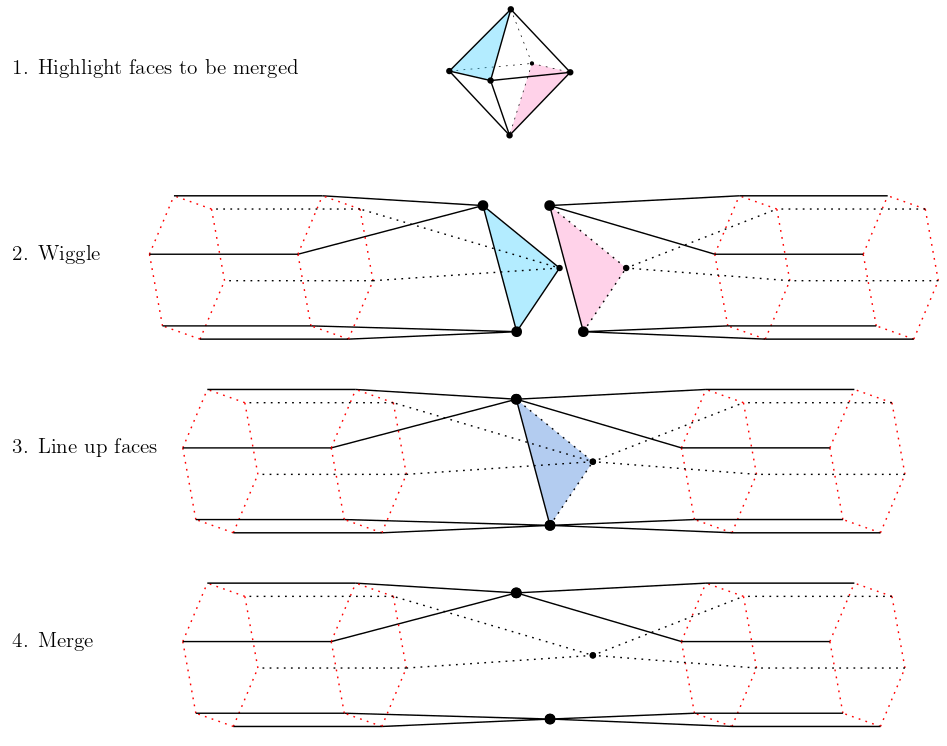

In 2D, we can merge pairs of edges. First, it must be possible to wiggle the shape until the two edges line up without anything in between them. Then, we 'merge' them by lining up the edges and removing the edges and the lined up vertices. The two faces of the edges become one if they weren't already.

This should be intuitive with an image. Given a square, we can merge opposite edges or adjacent edges:

When we merge adjacent edges of a square, we can get a vertex that connects an edge to itself. We call this shape a 'pointy circle'.

Note the requirement of "without anything in between them". This means that, for instance, we cannot merge the inner and outer edges of a 2D torus, because the torus itself is in between.

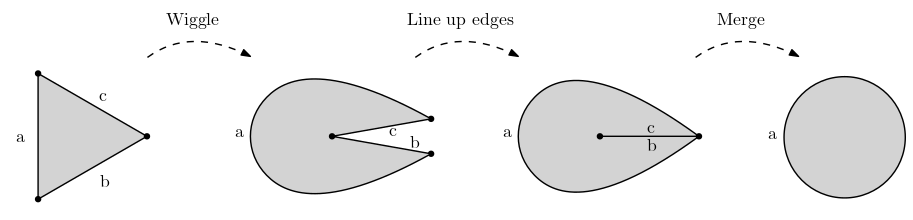

Merging two faces of a triangle results in a circle.

There are some edge cases to address.

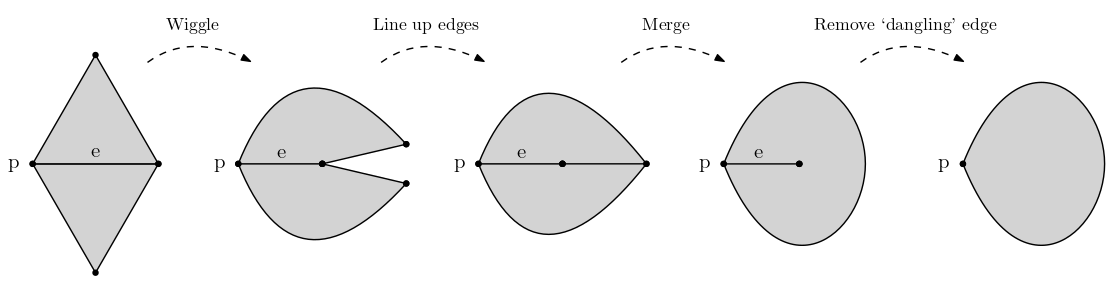

Edge Case 1: Dangling Edge

When merging two edges, we may end up with an edge that ends in the middle of a face. We call this a 'dangling edge'. By convention, we remove dangling edges as part of the merging operation, like e in the image below.

The remaining vertex, p, was not adjacent to either of the merged edges, so it stays.

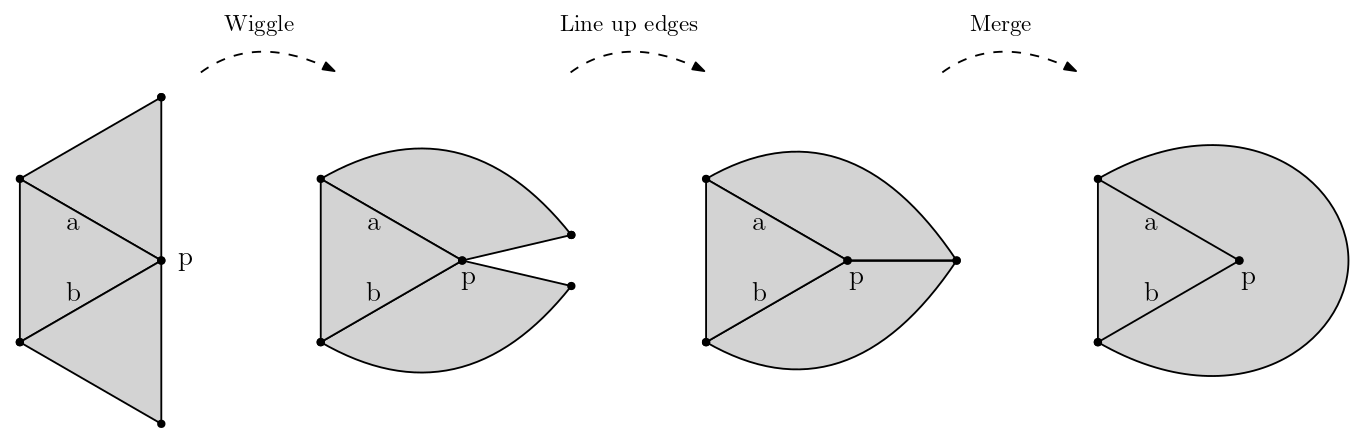

Edge Case 2: Surviving vertex

When merging two edges, the aligned vertices usually disappear. However, if a vertex is also connected to another edge which is not merged (or dangling), it will stay, like p in the image below. Edges a and b are not merged, so p stays.

3D Merging

Merging in 3D is the same as in 2D, but we merge faces instead of edges.

In order for two faces to be mergeable, they must be homeomorphic (same number of vertices and edges, same holes, etc) and it must be possible to wiggle them so they line up without anything in between them.

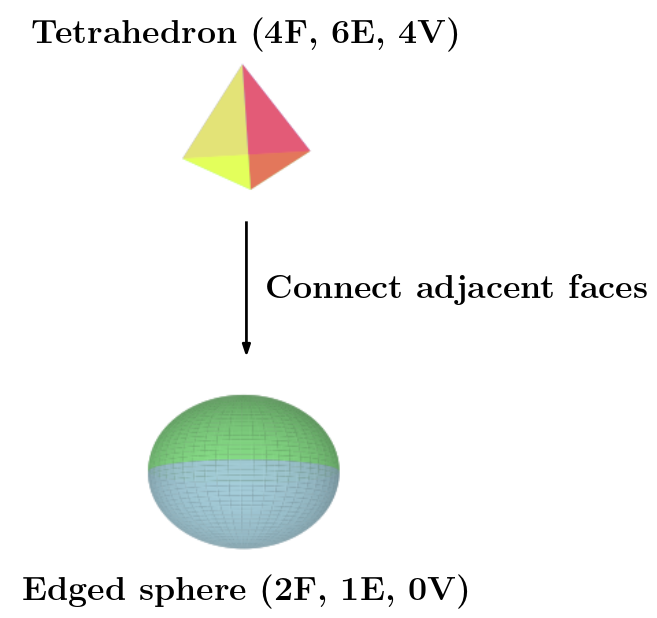

Tetrahedron

Characterizing the tetrahedron is trivial.

I'll use gifs to show 3D solids. The gifs show the solid from the front (left) and the back (right). They were made with this Python app I vibe coded.

Merging any two faces of a tetrahedron gives us an 'edged sphere' (a sphere with two faces, a single circular edge, and no vertices).

When I say "characterize the tetrahedron", I mean constructing a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of all the possible solids we can get by merging faces starting from a tetrahedron.

The tetrahedron DAG just has two nodes:

We say a solid is irreducible if it cannot go through any more merging operations. Irreducible solids correspond to leaves in the DAG.

Cube

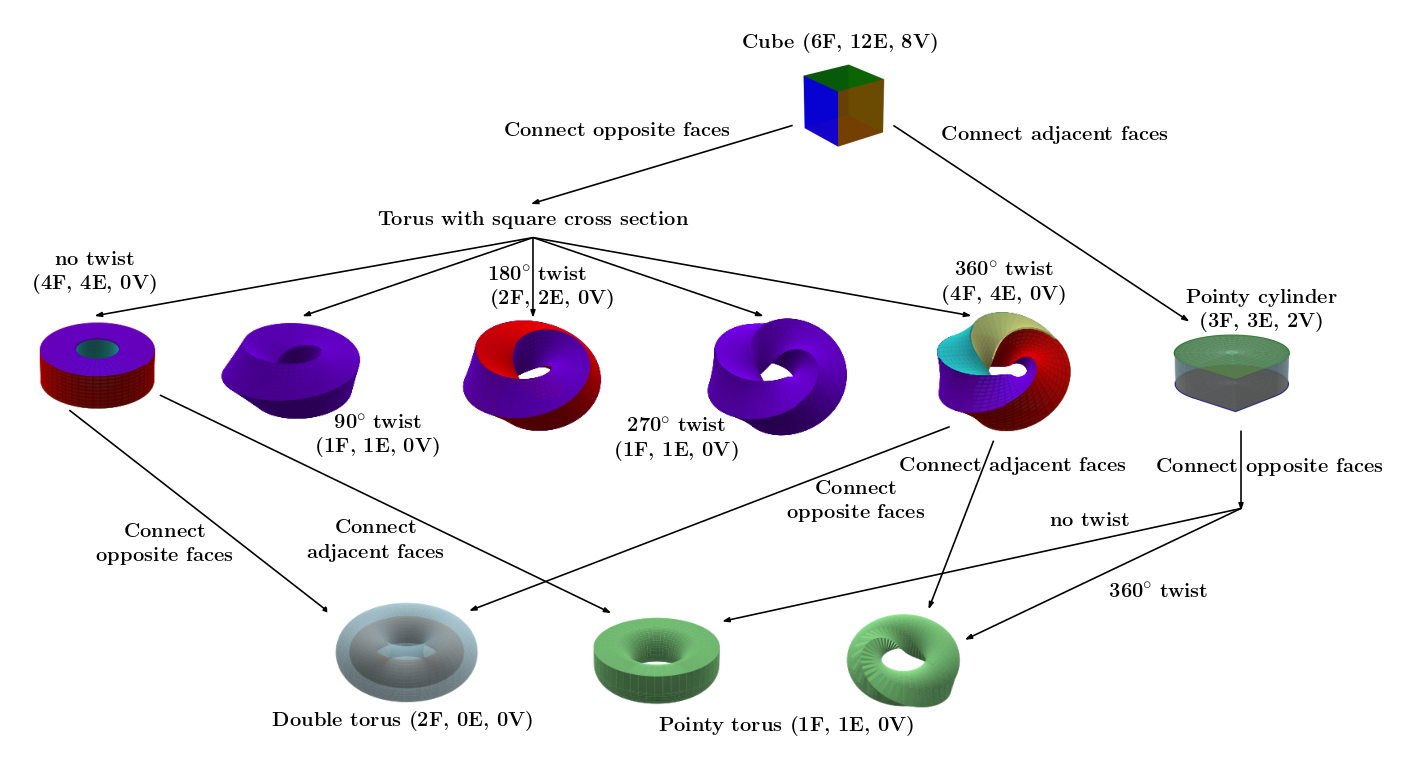

The cube is where things get interesting. For one, the cube DAG is infinite.

Cube branch 1: merging opposite faces

Analogously to how merging opposite edges of a square gives us a 2D torus, merging opposite faces of a cube results in a 3D torus with a square cross-section, which we call a 'square torus'.

However, when we wiggle the cube, we can twist it before lining up the faces. This still results in a torus with a square cross-section, but one which is not homeomorphic to the non-twisted torus. In fact, the number of faces changes depending on how much we twist it.

If we twist it 90 degrees, we get a single face:

If we twist it 180 degrees, we get two faces:

If we twist it 270 degrees, we get a single face again:

From that point on, the number of faces repeats. For instance, if we twist it 360 degrees, we get four faces again.

If we keep twisting it more, the number of faces repeats 4 -> 1 -> 2 -> 1 -> 4 -> 1 -> 2 -> 1 -> ..., but none of those solids are homeomorphic. So, by twisting, we can get an infinite number of different solids.

If we take the square torus without any twisting and merge adjacent faces, we get a torus where the cross-section is a pointy circle.

If we merge opposite faces instead, we get a torus with a torus cavity, i.e., a torus with a 2D-torus cross-section.

The square toruses that have 1 or 2 faces after twisting (e.g., with a 90 degree or 180 degree twist) are irreducible because there are not enough faces.

The square toruses that have 4 faces after twisting (e.g., with a 360 degree twist) are not irreducible, regardless of how much we twisted them:

- If we merge opposite faces, we get the a torus with a hole again. Surprisingly, this merge "undoes" the twisting.

- If we merge adjacent faces instead, we get a pointy-circle torus again, but this time the edge twists around the cross-section. The amount of twisting depends on how much we twisted the cube, so we can get an infinite number of different pointy-circle toruses. Here is the pointy-circle torus with 360 degree of twisting:

This covers every solid we can get from a cube by merging opposite faces.

Cube branch 2: merging adjacent faces

Starting from a cube, if we merge adjacent faces, we get a cylinder with a pointy-circle cross-section.

From there, we can merge the top and bottom faces of the cylinder to get a pointy-circle torus. When we do that, we can twist it to get all the same infinitely many pointy-circle toruses with twisting that we got from the square toruses.

Cube DAG

We can now complete the cube DAG:

Personally, what I find interesting about the cube DAG is how it is possible to reach the solids that require two steps in multiple ways.

Counting faces by cross-section sides and twists

Before getting to the other platonic solids, I'll go on a tangent to show a cute result:

A torus with a k-gon cross-section and n 'face twists' has GCD(k, n)

faces.

Where:

GCDis the greatest common divisor- A

k-gon is a polygon withksides - A face twist is a twist of

360/kdegrees. For instance, 1 face twist means that, in one full rotation of the torus, each face ends up one face over.

We already saw some examples with the square torus (a 4-gon torus):

0face twists (0 degrees):GCD(4, 0) = 4faces1face twist (90 degrees):GCD(4, 1) = 1face2face twists (180 degrees):GCD(4, 2) = 2faces3face twists (270 degrees):GCD(4, 3) = 1face4face twists (360 degrees):GCD(4, 4) = 4faces

This result also explains why the number of faces repeats as we twist the square torus further.

Here are some examples with a different k-gon, a 12-gon:

If you want to play with different k-gons and number of face twists, the source code for the Python app is here.

The argument for why the number of faces is GCD(k, n) is as follows:

Proof: Pick any cross-section of the torus, C. C is a k-gon, so we can label its edges with 0, 1, 2, ..., k-1 along the twist direction.

If we walk along a face of the torus, starting from C, edge 0, by the time we get back to C, we'll have moved n edges over in the twist direction. Since there are only k edges, that means we'll end up at edge n % k.

If we keep walking along the torus, we'll reach, edges 0, n % k, 2*n % k, 3*n % k, and so on, until we reach a number i*n that is a multiple of k and we get back to edge 0. All these edges belong to the same face of the torus. Thus, each face of the torus covers i edges of C, making the total number of faces k / i. Now we just need to see that k / i = GCD(k, n).

The number i*n is the first multiple of n that is also a multiple of k. In other words, i*n = LCM(k, n), where LCM is the least common multiple.

Recall the GCD-LCM identity: GCD(a, b) * LCM(a, b) = a * b.

Using that LCM(k, n) = i*n, we get that GCD(k, n) * (i*n) = k * n, so k / i = GCD(k, n). ∎

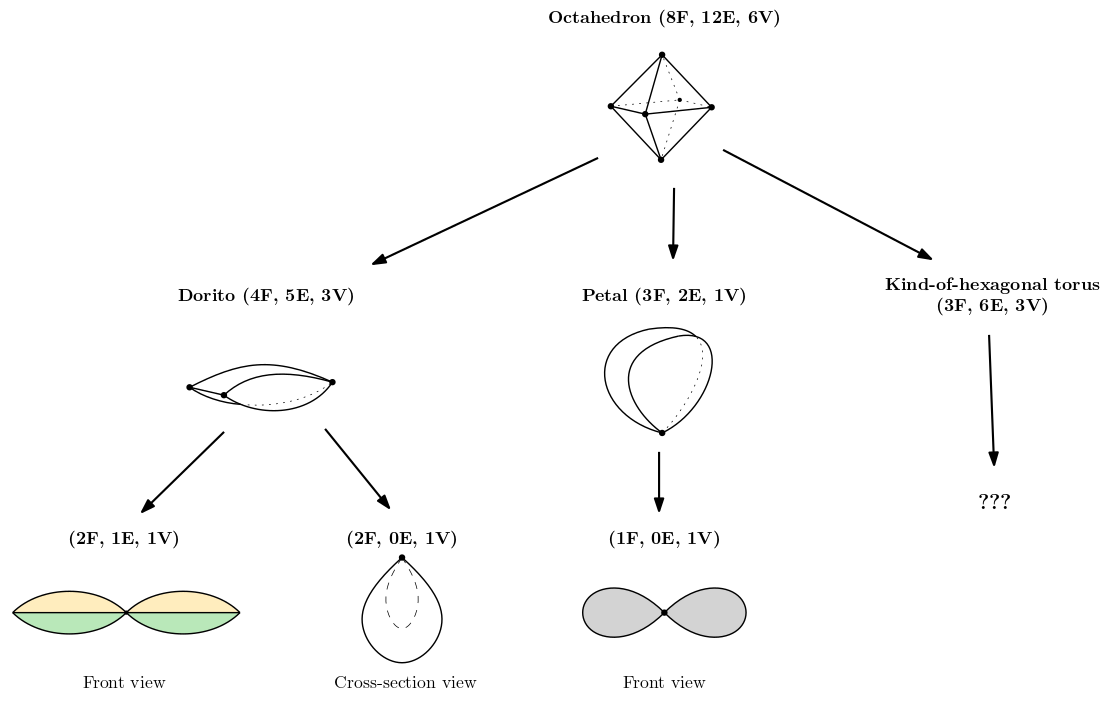

Octahedron (work in progress)

As of March 2025, I haven't finished the octahedron DAG yet.

Octahedron branch 1: merging edge-adjacent faces

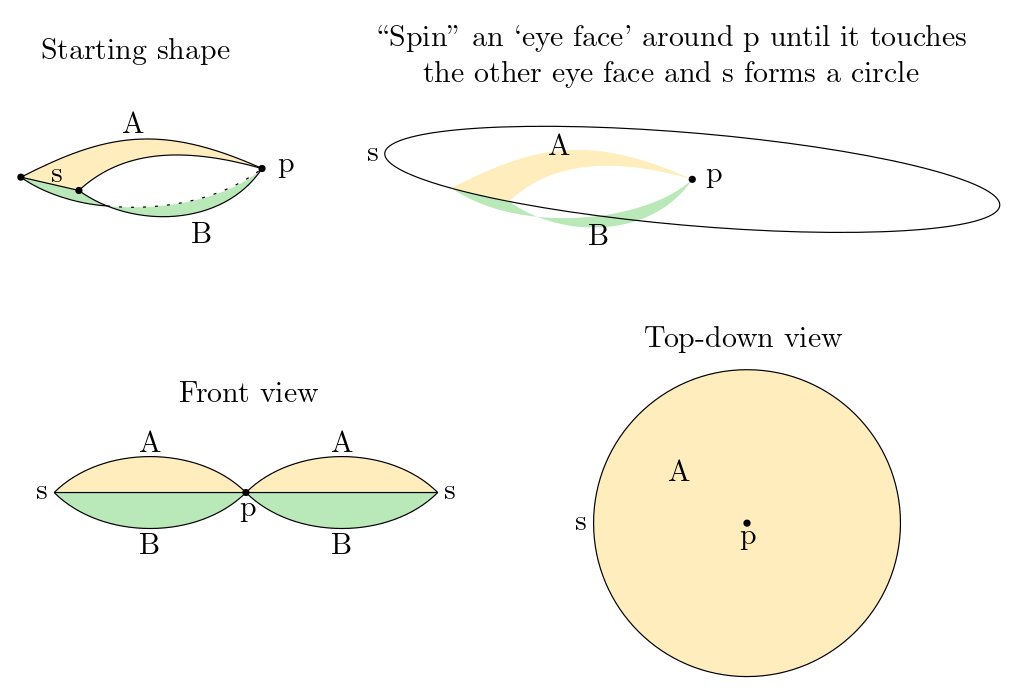

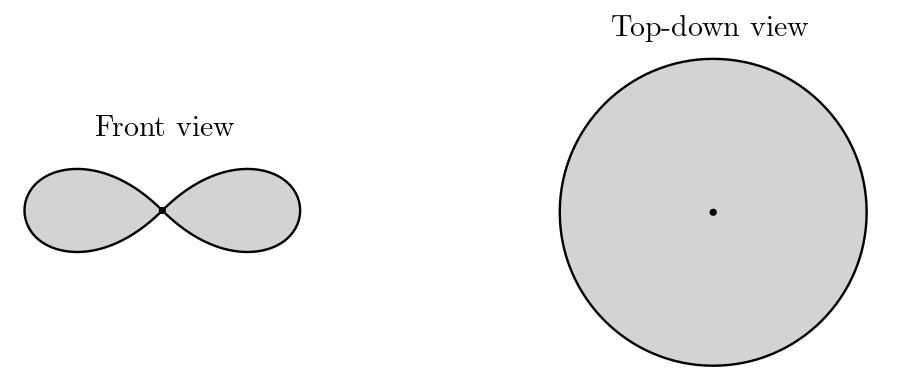

If we merge two faces sharing an edge, we get this shape with two triangle faces and two 2-gon or 'digon' faces (a closed shape with two edges) which I'll be calling 'eye' shapes:

Can anyone suggest a good name for this shape? I'll go with 'Dorito' for now.

If we merge the two 'eye' faces of the 'dorito', we get a kind of torus with a single point in the center instead of a hole, and an edge along the outside of the torus. Since the two eyes share a vertex, no twisting is possible.

Unfortunately, as I mentioned, I vibe coded the Python app to draw the 3D solids, and this is the limit of what I've managed to get Claude to draw. So, for the remaining faces I only have sketches or nothing at all.

If we merge the two triangle faces, it's hard to visualize what happens, but (I think) one of the eyes becomes an inner face and the other an outer face. The 'dorito' shape has a vertex shared by all four faces, so, since it is adjacent to the two 'eyes', which are not merged, it stays after the merge (see edge case 2 in merging). That means that the outer and inner face share a vertex.

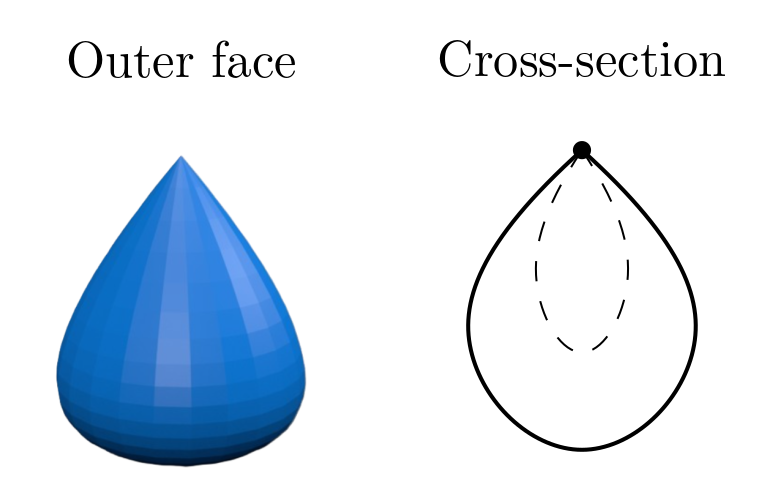

The final shape looks like a 3D 'teardrop' solid with a 'teardrop' cavity, where both teardrops share the top vertex.

Insert joke here about how the eyes turned into teardrops.

That's all we can do in the first branch of the octahedron DAG.

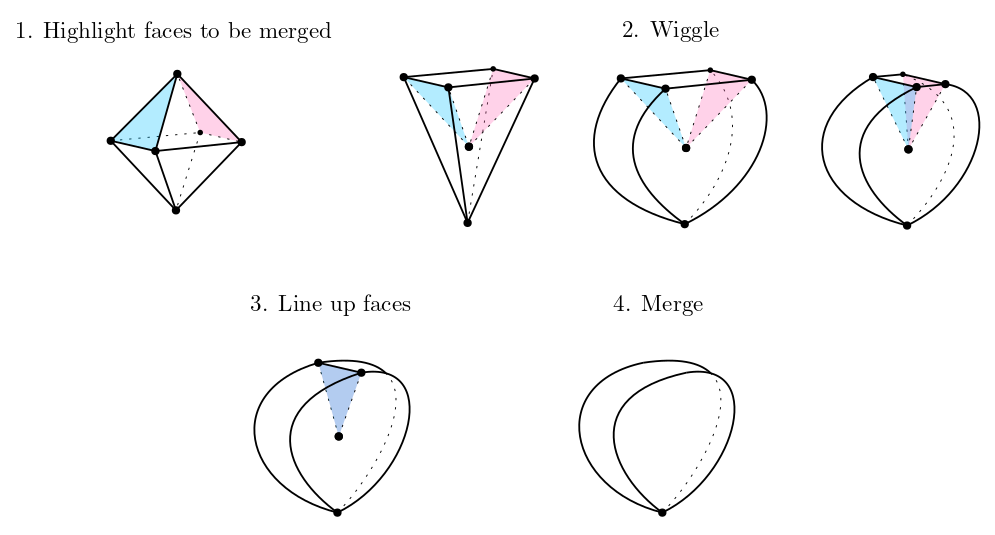

Octahedron branch 2: merging vertex-adjacent faces

If we merge two faces sharing a vertex, we get this shape, which I'll call the 'petal'.

The only thing we can do with the petal is merging the two pointy-circle faces sharing a vertex, which results in a torus with a single vertex in the center instead of a hole.

That ends this branch.

Octahedron branch 3: merging opposite faces

This is the most interesting branch. Anytime we merge two faces that don't share any edges or vertices, we form some kind of torus. In this case, I think it's a torus with a hexagonal cross-section, except for a single point in which three of the edges 'collapse' into vertices and the cross-section is a triangle (at least, that's one way to draw it -- it's not the only way). Here is my best attempt at sketching the 'collapse point':

If I counted correctly, this solid has 3 faces, 6 edges, and 3 vertices regardless of how much twisting we do. I'm not sure whether it is irreducible, and whether that depends on the amount of twisting.

Octahedron DAG

This is what I have so far:

Unlike the cube, we don't get any shared solids between the branches.

What's next?

I don't know much about the dodecahedron and icosahedron yet. What's clear is that I pushed the limit of both vibe coding and of the 2D drawing editor (the amazing Ipe). I think Blender is the right tool for this, and I'm actually curious enough about what these shapes look like that I started messing around with it. So far, I managed to make this (scuffed) two-faced solid, which I incorrectly thought could be obtained from the octahedron:

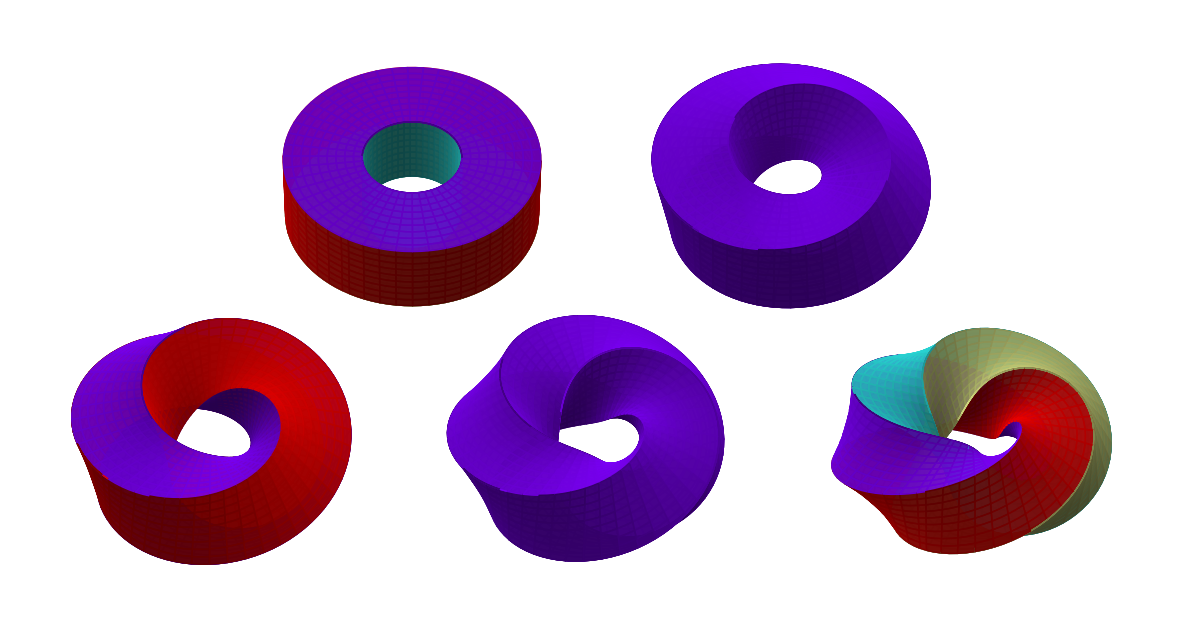

This project started from seeing this gif:

The concept of a solid mobius strip was new to me, and I started thinking about variations and how to construct them. That led me to the idea of starting with a cube and merging two faces. Then, I did something very common in math: I started thinking about possible generalizations.